Written by: Stephen Asare Abankwah, Prince Acheampong, Caleb Jeremie Dohou, and King Carl Tornam Duho

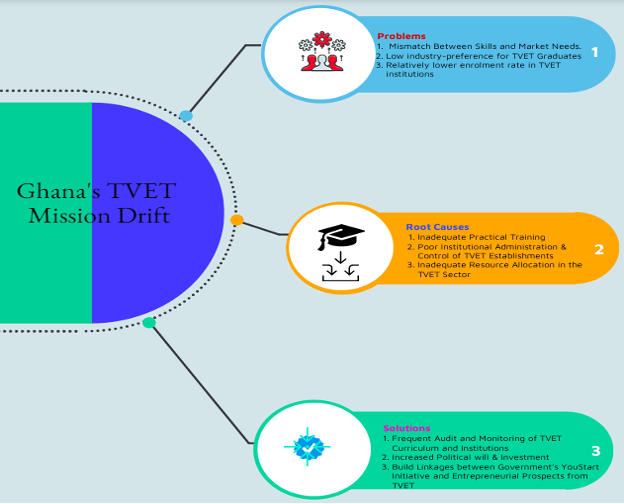

The evolution of Ghana’s TVET sector over the past decades has been tortuous and encumbered with a lot of challenges. Nonetheless, the future holds promise if policymakers and the government take a step back and consider how far apart the sector has drifted from its mission, identify the causes of the drift and implement lasting solutions.

1.0 Introduction

Goal 4 of the SDGs resonates a global commitment to make quality education equitable for all.[i] Achieving this goal― “ensuring inclusive and quality education and promoting lifelong learning” ― is not only a basic right but also crucial for a sustainable future. Despite experiencing a lot of hiccups on the road to meeting the 2030 target, some progress has been made in bridging the global education gap. Among the several milestones include the important role of Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) across the world. TVET has significant potential for socioeconomic transformation as it provides the platform for countries to develop their human capital. More importantly, TVET plays a pivotal role in solving the twin problems of poverty and inequality through increased employment opportunities for people, improving their income-earning capacities, and supporting the development of local industries. However, this is not without challenges as country-specific situations reveal little progress amid deep-seated structural deficiencies.

Like most developing nations, Ghana sits at a crossroads as it defines a new roadmap for its TVET system, the aim of which is to build a well-equipped and skilled workforce by linking the education system with the economy’s needs.[ii] Ghana’s TVET system has undergone several transformations over the years, however, the performance of the sector is far below expected outcomes. In addition, the trajectory of progress has fluctuated over the years, from its inception to date. With a population of more than 30 million people and a GDP of 2,363.30 USD per capita as of 2021, Ghana continues to grapple with rising unemployment as it is listed among the priority issues of the country. While the TVET enrolment rate has increased in recent years, unemployment levels continue to rise with the current unemployment rate going past 50% among the youth population.[iii] Between Q1 and Q2 2022, Ghana’s unemployment rate rose from 13.4% to 13.9%. Meanwhile, recent available TVET data shows that between 2015/2016 to 2019/2020, tertiary enrolment for all tertiary TVET providers in Ghana saw the highest enrolment (70,917) in the 2016/17 academic year and declined between the years 2017/2018 and 2018/19 academic years from 52,524 to 50,839 respectively.[iv]

The aim of the paper is to highlight the series of problems facing Ghana’s TVET system. The paper also explores the reasons for their emergence, while also recommending relevant solutions to change the status quo and ensure significant progress.

2.0 Problems Emanating from the TVET Mission Drift

Prioritising TVET as a major contributor to Ghana’s development agenda cannot be overemphasised. That notwithstanding, Ghana’s TVET landscape is faced with systemic challenges that continue to truncate the prospects for future success. The following highlights the problems arising due to the existing TVET mission drift.

Mismatch Between Skills and Market Needs:

Unlike academically-oriented education which keeps a somewhat fast pace with market needs (though faces challenges in this respect), there appears to be a rather slow catch-up within the TVET sector in Ghana. This has been a historical phenomenon. Meanwhile, the International Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (UNEVOC) indicates that the role of digitization remains paramount to the future of work as millions of jobs are changing and re-inventing.

According to the IFC (2019), the skills for the future include Email Communication, Data Analytics, Web Research, Accessing Government Online Services, Using Basic Software like google suites, Creating and Sharing Content (social media), Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, Online Transactions and Digital Marketing.[v] Similarly, following the boom in green industries, the frequency of research in this area has increased worldwide, and governments are building synergies with technical and vocational training, albeit research on this front remains low in Ghana.

Inevitably, the infrastructure and systems for TVET institutions cannot remain static. A survey collected from the 85 TVET institutions in Ghana on the responsiveness of TVET programmes to industry needs showed that only 29.4% of TVET programmes meet industry needs while 9.8% indicated that there were no visible linkages between TVET programmes and industry.[vi] This goes to show that market requirements are changing with such great momentum that the TVET curriculum has to be in continuous reorientation.

Low Industry Preference for TVET Graduates:

Industry preference for TVET graduates remains low as compared to those of university graduates. As is the case elsewhere, TVET in Ghana faces a lot of negative stereotypes already and these become a factor in employee selection. Generally, most parents and other stakeholders believe vocational education to rank lower than academic education. Thus, to avoid taking a risky gamble on whether employees fit a job portfolio, it is standard practice that employers consider the quality of training provided, and subtly consider the reputation of the school attended, and the career experience of graduates, among others as criteria for selection. Therefore, producing professionally successful TVET graduates is at the core of this problem.

Though in-roads have been made in engaging industries as significant players in the TVET system value chain, their involvement remains woefully low. This is corroborated by a recent survey conducted which showed that about 26% of respondents rated the industry’s interest in TVET to be very high, 22.4% rated it high, 12.9% rated it low and 11.8% rated it very low.[vii] However, 27.1% stated that they do not know about the interest of companies in TVET. As it stands now, there is low collaboration and engagement between industry and TVET institutions.

From a different angle, TVET graduates are considered by some employers over university graduates because they constitute a cheap labour force compared to their counterparts. There are many TVET career paths that require intense manual work and TVET graduates tend to be engaged at a low level even when they have built the skill set that requires their progress across the institutional ladder.

Relatively Lower Enrolment Rate to TVET Institutions:

The TVET sector has improved in recent years, however, a challenge that hinders the rapid growth of the sector is the relatively low enrolment of TVET institutions. Again, this is partly due to the perception and recognition of TVET among the population. Most young people dream of pursuing careers in academic fields such as medicine, law, accounting, economics, etc. Meanwhile, professions such as auto mechanics, hairdressing, and carpentry are considered poor alternatives and are low-paying.[viii] Therefore, people are disincentivized to consider careers in TVET. This is also emboldened by the government’s posture towards TVET education; the immense value of TVET education is not advertised as much. Thus, individuals most likely to enrol in TVET institutions are those who may have been declined admission into academic universities. An emphasis is not also placed on avenues for TVET graduates to be able to pursue advanced degrees later even in the academic track after proven experience in industries.

3.0 Root Causes of TVET mission drift in Ghana

Looking beyond the surface of the problems discussed above, it is clear that there are fundamental causes for the eventual drift of TVET in Ghana. Ignoring these issues would not effectively address the problems of the TVET system. Below are the major causes of TVET mission drift in Ghana

Inadequate Practical Training:

TVET promotes youth education access to all. The education system in Ghana has caused a paradigm shift in the mission of TVET in the sense that education which is accessible to all has been overly theoretical and less pragmatic. Theoretical knowledge does not provide one with technical job skills, unlike practical learning; a gap that TVET education is supposed to fill. Ansah & Kissi (2013), notes a pragmatic example that TVET learning centres like polytechnics are incapable of integrating conjectural training with useful exposure to creatively equip graduates for the industry.[ix] Owing to inadequate practical training, there has been a TVET mission drift in Ghana, for instance, the country’s nascent oil and gas industry as well as the upcoming renewable energy technologies are in urgent need of skilled workers, the absence of which will revert demand to foreign labour. That aside, reforms have largely focused on centrally altering a school system made up of an addiction to grammar–type education to the delinquency of technological and vocational instruction and externship, a condition seen as an educational preference (Aziabah, 2017).[x]

Poor Institutional Administration and Control of TVET Establishments:

Despite the continuous reforms in the TVET sector, there is negligible progress in the aspects related to administering quality TVET education parallel to that of university education. Ansah & Kissi (2013) argue that the management of TVET institutions in Ghana is ineffective and inefficient.[xi] Similarly, monitoring and evaluation, as well as supervision and quality assurance systems are inadequate. Kafle & Pfeiffer (2021) postulated that the paucity of surveillance and control of TVET establishments moves the tasks of Technical and Vocational Institutions away from their socio-economic goal which is the provision of qualified and skilled labour resources for the youth to have the dexterities for such an education.[xii] Frequent Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) Systems are the key to effective measurement of the entire TVET Reform Project or Programme and essential tools for ensuring quality improvement.

Inadequate Resource Allocation to the TVET Sector:

One of the major causes of the drift in the mission of the TVET sector in Ghana is the inadequate allocation of resources. More broadly, these inadequacies span huge infrastructural deficits to inadequate and up-to-date materials or training manuals and resources. TVET establishments lack the proper tools and equipment to be used in vocational training to keep up with the emerging skills of the changing times. Tied together with this is the fundamental issue of an underfunded TVET sector (Amedome & Fiagbe, 2013).[xiii] Due to these challenges, there is but a slow adaptation of the TVET system to match the accelerated changes in the world of work. This coincides with the slow adoption and utilisation of technological advancements to improve the relevance of courses taught and appropriate instructions given in TVET institutions.

4.0 Solutions to TVET Mission Drift in Ghana

Interventions to re-route Ghana’s TVET system towards its core mission are relevant to ensure that the optimum outcomes are achieved. It is important to note that, though Ghana’s TVET system faces a lot of challenges, it is possible to still revolutionise the sector to rub shoulders with those of developed countries. The following lists a number of solutions to address this teething problem.

Frequent Audit and Monitoring of TVET Curriculum and Institutions:

One of the ways to rectify the TVET mission drift is the need to frequently streamline or restructure the curriculum of TVET institutions to suit market-relevant demands. It is important for the Ghana TVET Service, Commission For Technical And Vocational Educational Training (COTVET), the National Vocational Training Institute (NVTI) under the Ministry of Employment and Labour Relations, Ghana Education Service (GES) and the Ministry of Education (MOE) to take pertinent actions to formulate a curriculum which is suitable to the economy’s social and economic needs; a curriculum that gives possibilities to augment access and equity; one that accommodates soft aptitudes and links TVET Institutions with the needs of the industries. Accordingly, the state should facilitate all industrial institutions to take part in scheduling the TVET curriculum as well as provide in-service and on-job-training programmes in those establishments (Kirior, 2017).[xiv] To acquire skills that match industry requirements, there should not be gaps in the implementation of competency–based training in the TVET curriculum. The skill of problem-solving should be in the curriculum to enhance entrepreneurship. There should also be increased monitoring and assessment of TVET institutions to ensure the increased quality of training and development of students. There should be a conscious effort to psych the children from early development at pre-primary and basic schools about the equally essential role of TVET routed career.

Increased Political Will & Investment:

Without political will/commitment, governments are bound to relegate positive interventions to the background. There should be a balance in the attention the government gives to the TVET sector as it does to institutions of higher learning. Increased political will could take the form of increased funding for the TVET sector. According to Kafle & Pfeiffer (2021), governments can enhance labour market outcomes by building a closer relationship between educators and employers.[xv] The government must be at the heart of driving a change in the status quo. There should be an initiative of the government to provide resources that will help improve TVET institutions and in turn, curb TVET mission drift in Ghana. Recently, Polytechnics in Ghana was transformed into technical universities (only in name); a move that has made it quite appealing for students to enrol in TVET institutions across the country. In fact, our checks reveal that aside from the HND-related courses that are a bit practical in nature, the degree courses being offered are churning out students with more theoretical content than the practical aspect which is expected from an institution of such nature. The most critical problem is also the influx of business programmes that TVET institutions are tempted to introduce which undermines their entire mission. Duty bearers should be committed to ensuring that TVET institutions and emerging TVET Universities like the Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development (AAMUSTED) do not shift their focus from their mandate.

Build Linkages between Government’s YouStart Initiative and Entrepreneurial Prospects from TVET:

In 2022, the government launched a GHS 1 billion YouStart initiative. The aim of the initiative is to build an entrepreneurial nation and create at least 1 million jobs for the youth in the next 3 years (2022 – 2025). One of the potent ways to ensure this is to build clear linkages between this initiative and the entrepreneurial prospects of TVET. Given the entrepreneurial focus of the TVET sector, and the potential of increasing the productivity of the country’s workforce, the YouStart initiative could be tailor-made to encourage the establishment of innovative business start-ups and foster a culture of entrepreneurship among graduates. Doing so, would change people’s perception and increase the enrolment rate in TVET institutions.

5.0 Conclusion

Ghana’s TVET system has great prospects to promote socio-economic transformation. However, this has been saddled with a lot of challenges that threaten to derail the TVET sector from future success. The drift in TVET mission results in several problems including the mismatch between skills and market needs, low industry preference for TVET graduates and a relatively lower enrolment rate in TVET institutions. Furthermore, the root causes of these problems include inadequate practical training, poor institutional and administrative control of TVET establishments, and inadequate resource allocation. However, to solve these problems, we contend that there should be increased political will and investment, frequent auditing of the TVET curriculum and the need to build linkages with the government’s YouStart Initiative.

****************

Acknowledgement & CRediT authorship contribution statement

This project was supported jointly by Dataking Consulting (Lab), Business and Economic Policy House as well as the VIT Centre for TVET Policy and Education, which are part of a Consortium. We declare no conflict of interest in conducting this analysis.

SAA: Conceptualization, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision; PA: Writing – Original Draft; CJD: Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision; KCTD: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision.

Authors Bio:

Stephen Asare Abankwah is a finance and economic expert with the Consortium. He undertakes multidisciplinary research, primarily focusing on development issues.

Prince Acheampong is an intern with the Consortium and holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Economics and Philosophy.

Caleb Jeremie Dohou is a development practitioner and data scientist. He is an honorary advisor to the Consortium.

King Carl Tornam Duho, ACMA CGMA CA is an accounting economist. His research has appeared on regional and international platforms.

References:

[i] UN (2019) “Review of SDG implementation and interrelations among goals: Discussion on SDG 4 – Quality education”, United Nations. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/23669BN_SDG4.pdf (Accessed on 17 March 2023)

[ii] UNEVOC (2016) “World TVET Database: Ghana”, Geneva: UNESCO-IBE. Available at: https://unevoc.unesco.org/wtdb/worldtvetdatabase_gha_en.pdf (Accessed on 17 March 2023)

[iii] Caggiano, M. (2017) “Ghana: challenges and opportunities of technical vocational education and training (TVET) system”, Sustainableskills.org. Available at: https://sustainableskills.org/ghana-challenges-opportunities-technical-vocational-education-training-system/72463/ (Accessed on 17 March 2023) [Caggiano]

[iv] CTVET (2021) “Ghana TVET Report”, Commission for Technical and Vocational Education and Training. Availablet at: https://ctvet.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/GHANA-TVET-REPORT-2021SIGNED.pdf (Accessed on 17 March 2023) [CTVET]

[v] World Bank (2019) “World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work”. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/816281518818814423/pdf/2019-WDR-Report.pdf (Accessed on 17 March 2023)

[vi] CTVET, supra

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Caggiano, supra

[ix] Ansah, S. K., & Kissi, E. (2013). TVET in Ghana: A tool for skill acquisition and industrial development. Journal of Education and Practice, 4(16), 172-180. [Ansah]

[x] Aziabah, M. A. (2017). The politics of educational reform in Ghana. Educational policy change and the persistence of academic bias in Ghana’s secondary education system. Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93761-8.

[xi] Ansah, supra

[xii] Kafle, A. P., & Pfeiffer, H. (2021). Revitalising Jiri Technical School in a Dramatically Changed Context: Governance, Management and Employability. Journal of Education and Research, 11(2), 6-27. [Kafle]

[xiii] Amedome, S. k. & Fiagbe, Y. (2013). Challenges facing technical and vocational education in Ghana. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 2(6), 253-255.

[xiv] Kirior, H. (2017). Improving the TVET Curriculum as a Strategy for Better Performance. Africa Journal of Technical & Vocational Education & Training, 2(1), 22-30.

[xv] Kafle, supra