Written by: Mwangi Maringa & Maina Maringa

Abstract

In the past, Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in Rwanda has tended to incline towards a supply driven model, with little recognition of the value of linkages with its markets, the demand side. Graduate absorption in the market which is as an important tool of determining the relevance of TVET has remained uncharted waters, while the participation of Industry in TVET has on the whole not been profiled. The conduct of graduate tracer surveys and employer satisfaction surveys is not visibly and systematically practiced. This paper reflects on the first steps taken in the on-going TVET reform in Rwanda spanning 2008-2013, to precisely redress these gaps.

Ecole Technique Officiels (ETOs) and Agroveternaires (EAVs) were surveyed using a complex sampling approach. Well-structured, coded, and graded interview schedules were administered appropriately by well-trained enumerators. Analysis relied upon pertinent descriptive and inferential statistical methods. The markets see value in TVET graduates but are not well prepared to absorb them. On their part, schools see the need for links with industry, but have not gained sufficient access for the crucial training component of Industrial Attachment Practice (IAP). Sensitisation of Industry to open up for this IAP should be carried out vigorously. There is an urgent need for a structured industrial attachment practice framework.

Keywords:

TVET quality, employer satisfaction, Industrial Attachment Practice (IAP), employability, practical skills, industrial liaison, industrial links, industry partnership (s).

Introduction

The Rwanda Vision 2020 had envisaged a drastic reduction of the extremely high percentage (90% in the year 2000) of the total labour force in the country that was tied up in subsistence agriculture and a conversion of the sector by the year 2020, to one that would be fully commercialised (GoR, MINECOFIN 2000). Expectedly, this would be achieved through support of the emergence of a middle-income group that is well educated and who through broadening and deepening several financial support instruments (Ibid) were expected to create wealth and generate employment through knowledge-based enterprises in the service sector, industry, communications, and information technology.

These enterprises would in turn support the government’s efforts to diversify the economic base of the country (ibid). It was projected that these efforts would reduce the agricultural sector’s contribution to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from its level of 45% in the year 2000 to about 32% in the year 2020. At the same time these efforts would result in an increase of the contribution of the industrial sector from 17% in the year 2000 to 26% in the year 2020, and that of the service sector from 38% in the year 2000 to 42% in the year 2020 (ibid). Successful modern economies today are based on efficient and competitive technologies.

This not only requires a well-educated population but one with technical skills that facilitate easy use and modification of developed technologies, as well as the invention of technologies peculiar to market needs. It is with this in mind that the quality of technical education (as evidenced by the employability of its graduates, and the forms of links training providers establish with industry) and the manner of its delivery were addressed here. Inherent to this interest was the aim of not only ensuring its ability to equip graduates with technical knowledge but of also developing in them entrepreneurial skills to develop and set up products and businesses, respectively.

Garvin’s (1988) cited in Halden (2013) advances five concepts or classifications of the various definitions of quality, as outlined by the Improvement Foundation (2011). The following two of the five concepts of quality bear direct relevance to quality of TVET here, vis:

- Quality as being manufacturing, or process based to the extent that quality is measured by the degree to which a product or service conforms to its intended design or specification. Quality as such then arises from the process (es) used; and in the case of TVET the training regime and its procedures, an integral part being the Industrial Attachment Practice (IAP) discussed in this paper.

- Quality as being user (or customer) based – a context dependent, contingent approach to quality. Quality here then is perceived as the capacity to satisfy needs, wants and desires of the user(s) in this case employers or industry. Given this perspective, quality in TVET would result in a graduate product that is employable as industry finds useful application of the graduates.

This perspective of quality for TVET is recognised in moderately common quality indicators among the wider array of quality indictors used in a great number of nations with competitive TVET, that include the European Union, the United Kingdom, Denmark, England, Germany, Ireland, New Zealand, Scotland, South Africa, Sweden, the Netherlands, and the United States of America. Common quality indicators in these countries basically fall into the following three groups (NCVER), 2007):

- Most common quality indicators: educational attainment, progression, human resources, learning environment, learner support, demographics, and inclusiveness.

- Moderately common quality indicators: assessment processes, financial resources, physical resources, course documentation, quality assurance systems, quality of teaching, quality of courses, stakeholder satisfaction, training cost effectiveness, access and equal opportunity, employment outcomes, management of training provision.

- Least common quality indicators: effectiveness of training, collaboration and cooperation, occupational health and safety, innovation, and development.

Liaison between Industry and Technical Institutions – A Descriptive Analysis

Discussion here probes various aspects of this interaction, and reaches out to vital considerations of this relationship, such as the value industry places on the worth of TVET graduates, ease of absorption of the graduates in the labour market, industry-training provider networks and mutuality as well as perceived benefits, profiles of trainee industry placement and responsiveness of industry to support this feature of training.

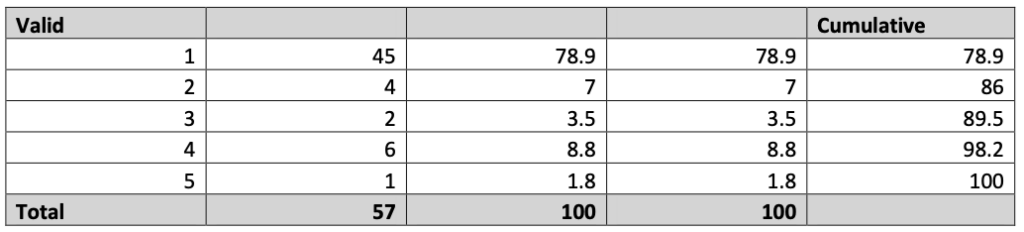

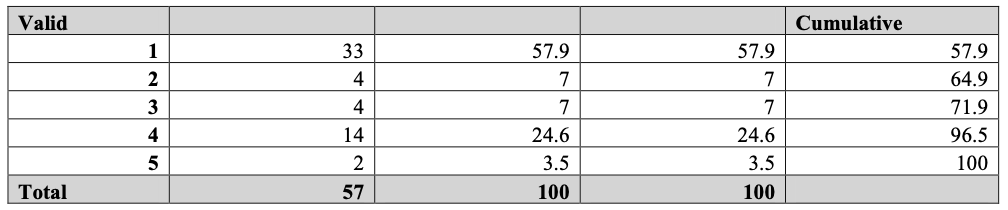

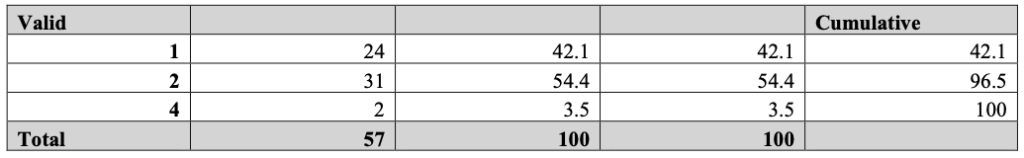

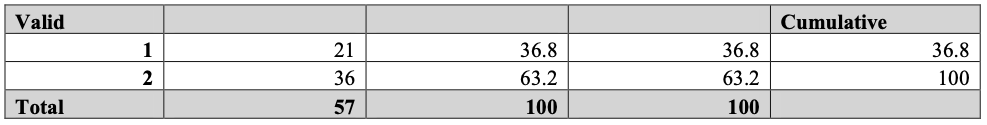

Table 1: Employability and Industrial Links: Good Reputation on the Employability of its Graduates

Figure 1: Employability and industrial Links: Good Reputation on the Employability of its Graduate (Ranking interpretation: 1: Agree, 2: Strongly Agree, 3: Unsure, 4: Disagree, 5: Strongly Disagree). Source: Mfinanga & Gakuba (Consultants), Maina & Mwangi (Researchers & Editors), 2008.

An overwhelming majority of the schools, 86.0% confirmed they had a good reputation on the employability of their graduates. Only 10.6% of the schools owned up to a converse poor reputation. Given the earlier trends seen in respect to the relevance of the education offered to market needs, and the qualification and skills profile of the teachers (Maina Maringa & Mwangi Maringa, 2010, 2011, 2015), this good reputation was surprising if it responded to job performance, unless it was attesting to good character and possibly other concerns such as teachability.

In 3.5% of the schools the head teachers did not know what reputation their graduates had. These school heads clearly did not take time to follow up on their graduates and therefore they clearly lacked an essential feedback system. It is critical that they mend this gap in their managerial responsibilities.

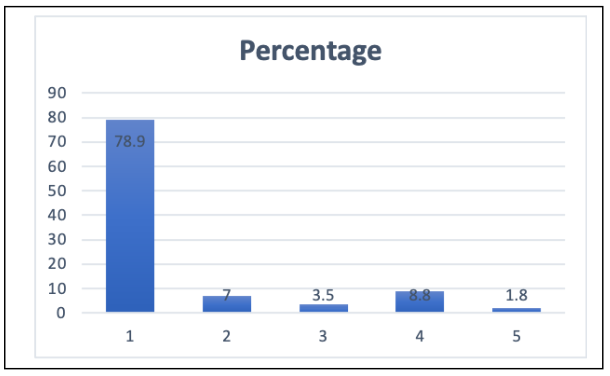

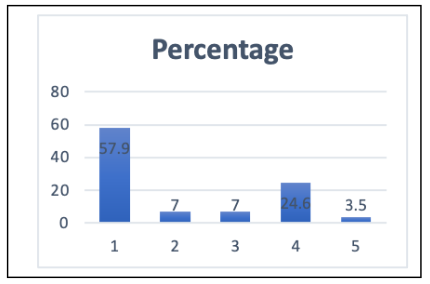

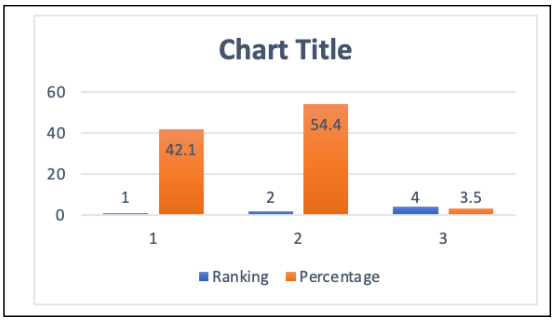

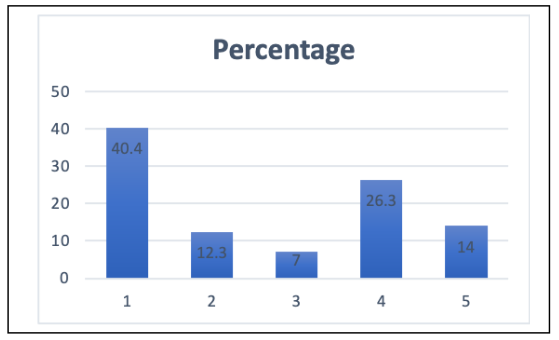

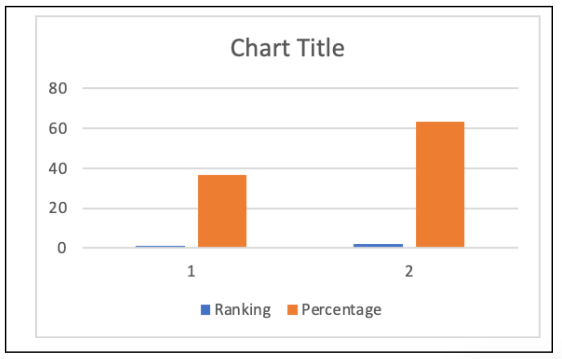

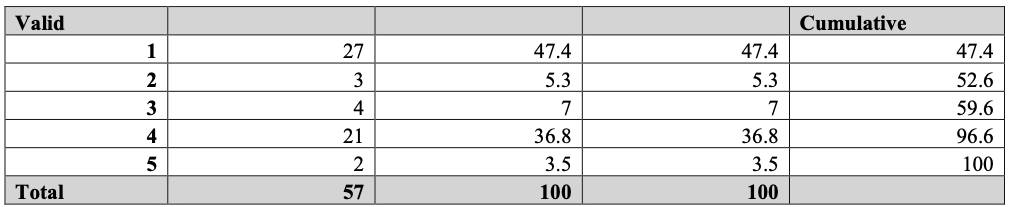

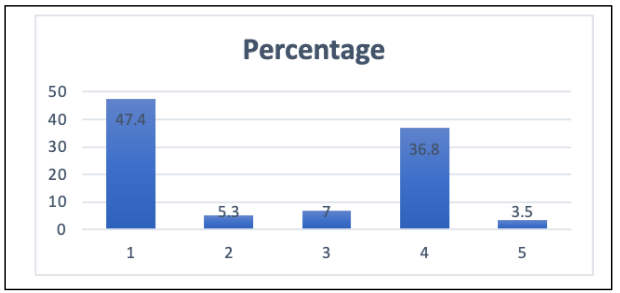

TABLE 2: Employability and Industrial Links: Graduates from the School get Jobs Easily

Figure 2: Employability and Industrial Links: Good Reputation on the Employability of its Graduate (Ranking interpretation: 1: Agree, 2: Strongly Agree, 3: Unsure, 4: Disagree, 5: Strongly Disagree). Source: Mfinanga & Gakuba (Consultants), Maina & Mwangi (Researchers & Editors), 2008.

Despite the good reputation observed above (table 1 & figure 1), graduates of these schools only found jobs easily in 45.6% of the instances. The alternative outlook that the job market was difficult to penetrate, would not respond to these particular graduates or was not sufficient was attested to by the report from 42.2% of the schools that their graduates did not obtain jobs easily.

A startling 12.3% of the schools had head teachers with no idea of the employability of their graduates, either because they did not care, or because they did not recognise the importance of these surveys. This is an attitude that needed to be reversed with urgency so that students would not victimised at the altar of negligence and poor networking on the part of the management of schools.

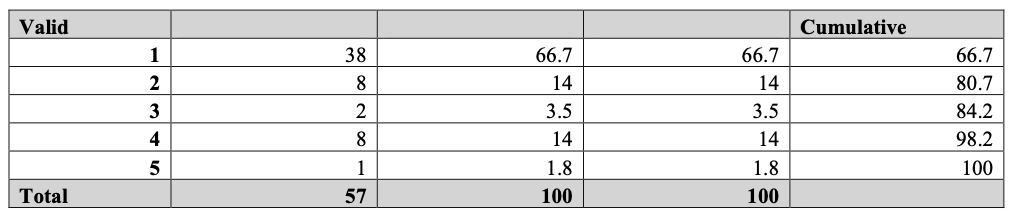

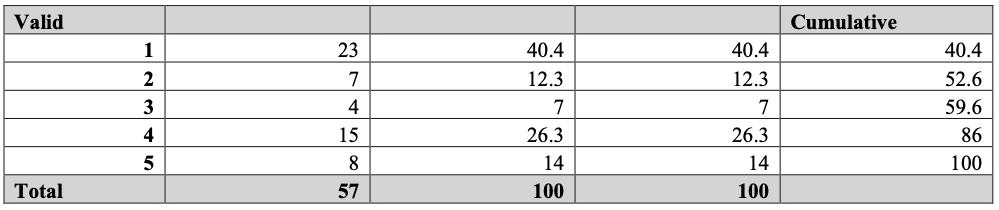

Table 3: Employability and Industrial Links: Good Working Links with Industries

Figure 3: Employability and Industrial Links: Good Working Links with Industries (Ranking interpretation: 1: Agree, 2: Strongly Agree, 3: Unsure, 4: Disagree, 5: Strongly Disagree). Source: Mfinanga & Gakuba (Consultants), Maina & Mwangi (Researchers & Editors), 2008.

A good 64.9% of the schools reported having good working links with related industry. Another conspicuous 28.1% had no such links, while 7.0% were led by head teachers who had no knowledge of their status either way. Such Heads who made little effort to affiliate schools with industry could not be expected to set useful standards in the schools, neither would they be able to introduce relevance in the programmes to market needs. A change of attitude in such instances was advisable.

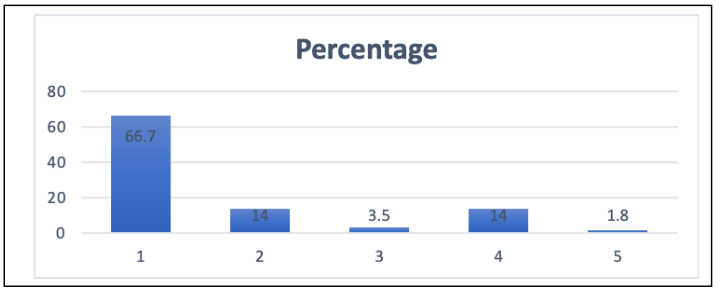

Table 4: Employability and Industrial Links: School Industrial Links Benefit both School and Industry

Figure 4: Employability and Industrial Links: School Industrial Links Benefit both School and Industry (Ranking interpretation: 1: Agree, 2: Strongly Agree, 3: Unsure, 4: Disagree, 5: Strongly Disagree). Source: Mfinanga & Gakuba (Consultants), Maina & Mwangi (Researchers & Editors), 2008.

There was a clear recognition that school-industrial links benefited both the schools and the industry in 80.7% of the schools visited. These links seemed to produce no benefits in 15.8% of the schools, a matter that needed further inquiry to determine if really these latter schools had set up clear links, and if so why then they would fail to produce the desired mutual benefits of improved training and better employees. A perceptible 3.5% of the schools were led by head teachers who did not know whether or not the links had value. Such a posture was inimical to the relevance and good performance of the schools and called for to be urgent remedy.

Table 5: Employability and Industrial Links: Part of the Requirements of the School Training Programmes is Industrial Training (Industrial

Attachment Practice)

Figure 5: Employability and Industrial links: Part of the Requirements of the School Training Programmes is Industrial Training – Industrial Attachment Practice (Ranking interpretation: 1: Agree, 2: Strongly Agree, 3: Unsure, 4: Disagree, 5: Strongly Disagree). Source: Mfinanga & Gakuba (Consultants), Maina & Mwangi (Researchers & Editors), 2008.

Schools overwhelmingly had made industrial training a part of their training programme in 96.5% of the schools surveyed. Only in 3.5% of the schools had failed so far to integrate industrial training into their training curriculum, and these needed to be urged to get on board like all the rest of the schools.

Table 6: Employability and Industrial Links: Student Placement for Industrial Training (Industrial Attachment Practice)

Figure 6: Employability and Industrial Links: Student Placement for Industrial Training – Industrial Attachment Practice (Ranking interpretation: 1: Agree, 2: Strongly Agree, 3: Unsure, 4: Disagree, 5: Strongly Disagree). Source: Mfinanga & Gakuba (Consultants), Maina & Mwangi (Researchers & Editors), 2008.

Student placement for industrial training though was not easy with only 52.7% of the schools reporting success, while a substantial 40.3% were not able to obtain any placements. In 7.0% of the schools the head teachers did not know whether or not their schools had in the past been able to obtain placement for their students in industries. Once more this reflected managerial negligence or indifference, a matter that ought not be allowed to continue unchecked.

Table 7: Employability and Industrial Links: Industrial Training (Industrial Attachment Practice) is the best way of Developing Practical Skills in Students

Figure 7: Employability and Industrial Links: Industrial Training (Industrial a

Attachment Practice) is the best way of Developing Practical Skills in Students (Ranking interpretation: 1: Agree, 2: Strongly Agree, 3: Unsure, 4: Disagree, 5: Strongly Disagree). Source: Mfinanga & Gakuba (Consultants), Maina & Mwangi (Researchers & Editors), 2008.

There was overwhelming consensus that industrial training was the best way of developing practical skills in students in 100.0% of the schools. Given this comprehensive understanding, what was needed then was facilitation and the setting up of necessary industrial data banks, which exercise would then be followed up with actual linkages.

Table 8: Employability and Industrial Links: Cooperation from Industries

Figure 8: Employability and Industrial Links: Cooperation from Industries (Ranking interpretation: 1: Agree, 2: Strongly Agree, 3: Unsure, 4: Disagree, 5: Strongly Disagree). Source: Mfinanga & Gakuba (Consultants), Maina & Mwangi (Researchers & Editors), 2008.

Cooperation from industries was only assured in 52.6% of the schools; with another 40.3% confirming that this cooperation was hard to come by. A conspicuous 7.0% of the schools were led by head teachers who did not know their status in these regards; a sad state of affairs that portrayed management as either inept or disinterested. Whichever way, these attitudes needed to be reformed at the earliest moment to avoid compromising relevance and standards in the schools.

Discussions & Findings

Only 40.9% of industry had links with training institutions. Another 18.2% did not know whether or not they had this liaison. There was an equal 40.9% of industry who reported not having any links with schools. The level of involvement of industry in training was low and this must surely have been affecting the relevance of curriculum taught to the needs of industry, the induction of necessary practical skills and also the availability of industrial training opportunities for students to touch base with the realities of their professions while still in school.

Industry liaison with training institutions that had the desired research component was only evidenced in 11.8% of the instances. A proportion of 23.5% of industry reported to have no idea about whether liaison was anchored on research or not. Another proportion, 44.0% of industry, the greater one of all three had no research links with training institutions. With these unfavourable statistics, the expected innovation and transformation of the methods of production were not realistically achievable. As was now clearly a common trend, this general statement was not anchored at the level of specialisations in the disciplines of, mechanical engineering, civil engineering, electrical engineering, electronic engineering, computer and ICT engineering, hospitality services and tourism, administration, accounting, agro-veterinary, and medicine.

Industry totally denied any certainty either way whether its links with trainers in schools had or did not have a research component. Clearly, the research component of industrial links between schools and industry was non-existent; otherwise, the industries would have been quite well aware of it at the specific level of specialisations of partnership or linkage. Appropriate empirical solutions to challenges of production and localised technological innovation and transfer were in this way jeopardised. Though industry avowed that it had links of a research nature, this assertion was not authenticated. This claim by industry was therefore inconsistent, undermining the worth of opinions on industrial links by industry.

A modest majority of 53.3% of industry had industrial training links with training institutions, which was consistent with the level of general industrial links so far identified. There were 33.3% of industries that did not have such links, and another 13.3% who did not know whether or not such links existed. The latter group really needed to take time to know their own organisation and activities, in order to steer their firms in any particular direction. These groups of industry were not a good source of opinion on training and links as they clearly were not concerned about their training responsibility.

The involvement of industry in industrial training of students that was declared in the survey faltered completely when tested at the level of specialisations in the disciplines of, mechanical engineering, civil engineering, electrical engineering, electronic engineering computer and ICT engineering, hospitality services and tourism, administration, accounting, agro-veterinary, and medicine. In a sense therefore, industrial links could be taken as being absent as they were declared to occur generaly but not in specific disciplines; at which level here, it emerged that not a single industry was aware or such training being in place.

A paltry 12.5% of industries confirmed being involved in the development of syllabi in schools. A considerable 33.3% of them did not know whether or not they were involved. This latter observation was truly a surprising stance that confounded understanding and one which needed to be reversed. Most of industry (66.7%) had no such links with training institutions. Both industry and schools ought to be encouraged to link up as partners in training.

It was critical for both to realize their intertwined destinies and to recongnise that without active involvement in one another’s activities they would lose the moral right to comment; as such comments could only at best be ill informed and often times, constitute a form of destructive criticism. They both needed to be willing to follow through their comments and criticism with positive practical remedial contributions. Only 16.7% of industry had links with institutions that were service based, with industry servicing the institutions. A surprising 20.8% were not certain if or not they had such links. for This poise, for firms not to know the activities they were supposed to be involved in was not tolerable at all. The great majority of industry (59.5%) had no such links.

A meagre 40.0% of industries believed that there was a technical or professional institutions verses industry partnership in the country, as opposed to 24.0% who thought otherwise, with another 36.0% who had no idea either way. These links needed proactive and heightened publicity with clear programmes of implementation. Whereas industries projected a relatively low-key profile of technical (professional) institution/ industry involvement, most (84.0%) were convinced of the worth of these partnerships and the need to improve them.

The disturbing trend of industry without opinion on this matter in 16.0% of the sector was noted here too. These required to be canvassed, and also re-educated in order to alter this unacceptable disposition. A majority of industries (68.0%) happily were willing to participate in setting up or strengthening any existing technical institution/industry partnerships. Only 4.0% were hostile to such initiatives and these could be won over with the right approaches. Indecision whether to or not participate was recorded in 28.0% of industry. This, though an awkward stance represented the part of industry that was waiting to be convinced of the value of involvement or participation.

A good majority (72.0%) of industry was willing to support technical institutions/industry partnerships. A conspicuous 24.0% could not decide on their stance, while 4.0% were not willing to enter such undertakings. The latter two groups represented target groups to be sensitised and won over, with proper strategies. Not all industry saw its partnership with training institutions as expanding to take up a regulatory role of standards nationally. Only 56.0% saw this as their role, while 8.0% differed, with another 36.0% waiting to be convinced either way.

This was not a bad start as the balance of 44.0% could be won over with proper marketing and re-education. The 56.0% critical mass was well disposed to immediately receive orientation on the responsibility of such a regulatory role in respect of setting standards and monitoring. It is this critical mass that would serve as an initial market for recruitment into national regulatory bodies. A marginally higher proportion of industry (64.0%) perceived that the role of technical institutions/industry partnership was to ensure relevance of courses in the nation’s training institutions. Only 4.0% were opposed to this thinking, while another 32.0% were waiting to be convinced either way. These latter two groups then formed target groups for a well-orchestrated re-orientation campaign.

A majority of industry (72.0%) clearly expected to see students from training institutions contribute to the creation of knowledge and skills in the course of training and to transfer this to industry through the established links. There was a recalcitrant 8.0% who thought otherwise, and another 20.0% who were undecided either way. These latter two groups could be won over strategically. Industries were less convinced of their role to transfer technologies to students in training institutions. There were 68.0% who saw this as the role of industries in the technical institution/industry partnership. The converse perception was held by 12.0% of industry, while 20.0% of them were undecided. Once more the target group whose attitude needed re-orientation through sensitisation campaigns was clear.

There was a modest 45.8% of industry who accepted the role of industry in the technical institutions/industry partnership as one of guaranteeing employment for the graduates. A considerable 40.7% refused to enter judgment, or make a commitment, one way or another, with 12.5% of industry rejecting this perception outright. Some work and consultation would undoubtedly be needed for industry to fully accept its role as job creators in national building, either through direct employment or in the form of facilitation or partnerships.

A great majority of Industry (82.6%) recognised the need to set up professional regulatory bodies in various technical institutions/industry fields that existed in the country. There were 17.4% of the industries though that were uncertain about such bodies being set up. These did not pose an insurmountable challenge especially given the majority alternative poise of the 82.6% majority industry. The latter ones could be won over with proper sensitisation.

Industry also overwhelmingly (72.0%) accepted the role of the technical institution/industry partnership to regulate standards of training. Only a meagre 4.0% were opposed to this thinking, with 24.0% not able to make up their mind either way. These latter two categories then constituted the population to be canvassed. Participation of industry in the regulation of training standards was otherwise well endorsed and it could proceed on, being assured of support and participation from industry. The same distribution of opinion (72.0% in favour, 4.0% against, and 24.0% undecided) was seen in the aspect of the technical institution/industry partnership ensuring relevance of courses offered in technical institutions. Once more then quality assurance of courses could proceed on with the blessing and assured participation of industry.

An overwhelming 84.0% of industry perceived the role of technical institution/industry partnerships as overseeing apprenticeship training of qualifying graduates, while 16.0% could not make up their mind on the matter. There were no dissenting industries on this issue. This was a good endorsement of an essential aspect of professional training after formal school that ensures proper and realistic practical applications of the skills and knowledge learned.

A convincing though lesser majority of industry (64.0%) was willing for this partnership of technical institutions and industry to take up regulation of practice in the field in order to attain acceptable professional standards. A small minority of 4.0% disagreed, while 32.0% were unable to make up their minds either way. Recruitment of more support was a fertile field if approached with tact and the latter two categories could still be brought across to the desired understanding. This role of industry in partnership with training institutions could nevertheless proceed on considering the 64.0% majority endorsement noted here.

The call for financial commitment of industry to support training of students received a low-key support with only 34.8% of industry showing a willingness to take up commitment. Another 21.7% could not choose whether or not to make a financial commitment. There was a considerable proportion of industry (43.5%) that decidedly would not make any such a commitment. Clearly, this engagement option lacked enthusiastic support. Alternative financing to at least kick-start the venture would have to be explored further until sufficient interest was generated in industry. It was necessary roll out for a clear rationale that explained the expected benefits of industry taking up this responsibility. Incentives such as tax holidays or privileged access for industries that agreed to participate were items to be given some serious consideration.

Conclusions & Recommendations

Overall, 86.0% of the schools reported a good reputation of their graduates, but job openings appeared to be constrained, with only 45.6% of the schools reporting that their students could find jobs easily. The majority of schools, 80.7% recognised the mutual benefits of industrial links, while 64.9% followed up and set up good industrial with industry. Most schools (96.5 %) had gone further to make industrial attachment practice intrinsic to the training of their students.

Whereas 100% of the schools recognised that using industrial attachment training was the best way of developing practical skills in trainees; student placement in industries for attachment remained a challenge with a modest 52.7% reporting accomplishment. Cooperation from industries on the other hand, was only assured in 52.6% of the schools. As a result, more work was needed in order to forge more effective links between schools and industry. It was necessary that industries were sensitised to their roles and responsibilities on the training of their would-be employees so they could avail their full cooperation.

Schools needed to know their status regarding any of the issues probed here on industrial training links. As a priority any management of schools that had displayed ignorance of these issues needed to therefore revise its focus accordingly.

References

- Ministry of Finance & Economic Planning (MINECOFIN), “Vision 2020”, Government of Rwanda (GoR), July 2000, Kigali.

- Morris, A. Halden (PhD, P.E), 2013, “Quality Assurance for TVET in the Caribbean: An example of best practices”, IVETA 2013, Quality Assurance in Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET), Caribbean Curriculum, Vol. 21, 2013, 121-148, December 3-4, 2013.

- Garvin, D. A. (1988). Managing quality: The strategic and competitive edge. New York, NY: Free Press.

- National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER), 2007, “A guide to Vocational Education and Training in Australia”, NCVER, South Australia.

- Mfinanga, Joseph & Gakuba, Theogene Kayiranga (Consultants), Maina Maringa & Mwangi Maringa (Researchers & Editors), “Strategic Plan for Technical Education in Rwanda for the years 2008 – 2012 (unpublished technical report)”, November 2008, Kigali.

- Maina Maringa and Mwangi Maringa, 2010, “Improvement of Technical Education in Public Technical Secondary Schools (Ecole Technique Officiel – ETOs) in Rwanda”, Journal of Technical Education and Training (JTET, Vol. 2, Issue 1, June 8 2010), http://penerbit.uthm.edu.my/ejournal/index.php/journal/jtet/79.

- Maina Maringa and Mwangi Maringa, 2010, “A Quality Indicator Guided Review of TVET in Selected Ecole Technique Officiel (ETOs) and Ecole Agroveterrnaire (EAVS) in Rwanda”, The African Journal of Technical and Vocational Education Training (AfriTVET, Vol. 1 No. 1, April 2011), http://www.fimen.net/AfriTVEThompage.html .

- Maina Maringa and Mwangi Maringa, 2010, “Effectiveness of Rwandan TVET: Trainer Competence and Motivation in the Ecole Technique Officiel (ETOs) and Ecole Agroveterrnaire (EAVS), The African Journal of Technical and Vocational Education Training (AfriTVET, Vol 2.No.1. 2015), http://www.fimen.net/AfriTVEThompage.html