By Andreas Reinsch and Dr. John Osoro Nyangweta1

Abstract

Following international developments and aspirations to improve the TVET sectors around the globe in anticipation of major technological change and increased international competition; the Government of Kenya appreciates the key function played by TVET Institutions and Technical Universities in imparting technical and hands-on skills that is prerequisite for priority sectors in attainment of Kenya Vision 2030 and the “Big Four Agenda”.

The Technology and innovation are pre-requisites for the youth unemployment, motivation for entrepreneurship, creation of wealth as well as the building and development of human resources required for the transition for industrialization and knowledge-based economy, cannot be underestimated. To this end, Vision 2030 and the “Big Four Agenda” are strategic milestones required in line with the national development agenda.

The Vision 2030 proposes the intensification of the application of hands-on skills to increase industrial output and productivity in terms of added value and quality. Kenya has highly cherished the necessity for innovation and technology as key drivers for socio-economic development. This has been the magic behind the massive economic growth and development of the Southeast Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan) and other economic powers, such as India and China.

Kenya is seen by many as a powerhouse of Africa and this is true from many perspectives. For Kenya the time has come to capitalise on its potential and to catch up with the most advanced economic powers around the globe. Achieving this, Kenya will be well-placed to actively participate in the expected sustainable economic rising of Sub-Saharan Africa.

1. Introduction

Why do we need quality assurance in technical and vocational education and training (TVET)? This is basically, because of the imperative requirements of labour market, regional and global developments as well as the complexity of technological developments and in continuous economical change as well as global competition for resources, investments and markets.

Quality assurance in education and training is fundamental for the long-term success of the national economy. A solid foundation of competent workers at all qualification levels will be required to keep the industry going and to ensure Kenya’s competitiveness.

The constitution of Kenya as well as the Kenya Vision 2030 emphasize the role of TVET as the engine of the economy producing adequate middle level professionals. Kenya is building a modernized robust and effective TVET system producing a competent workforce, whose competences are aligned and assessed against benchmark industry-driven internationally accepted standards of occupational competence with the target to educate and train competent2 graduates in all industries, who are ready to master technology and the innovations required for the creation of employment, entrepreneurship, and wealth. Priority sectors of the “Big Four Agenda” are manufacturing, health, agriculture, and housing.

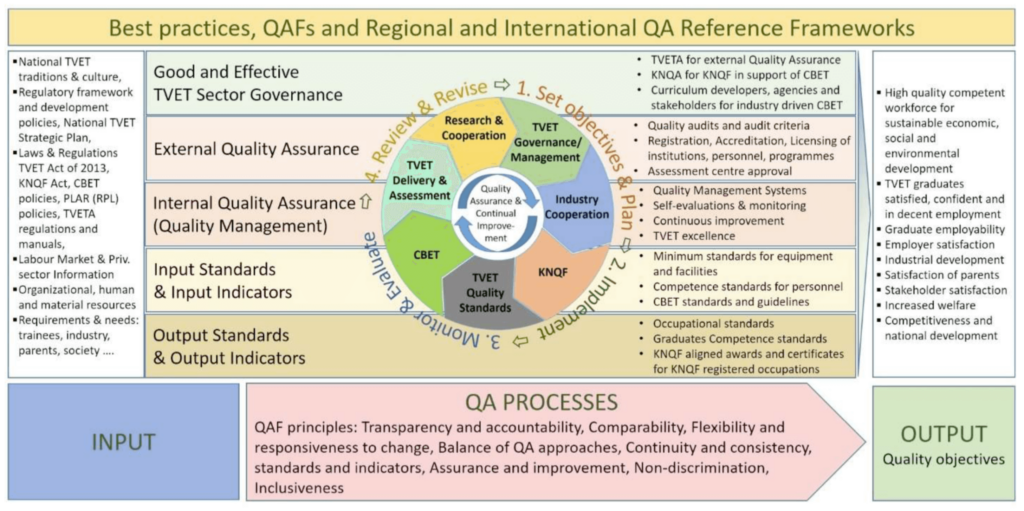

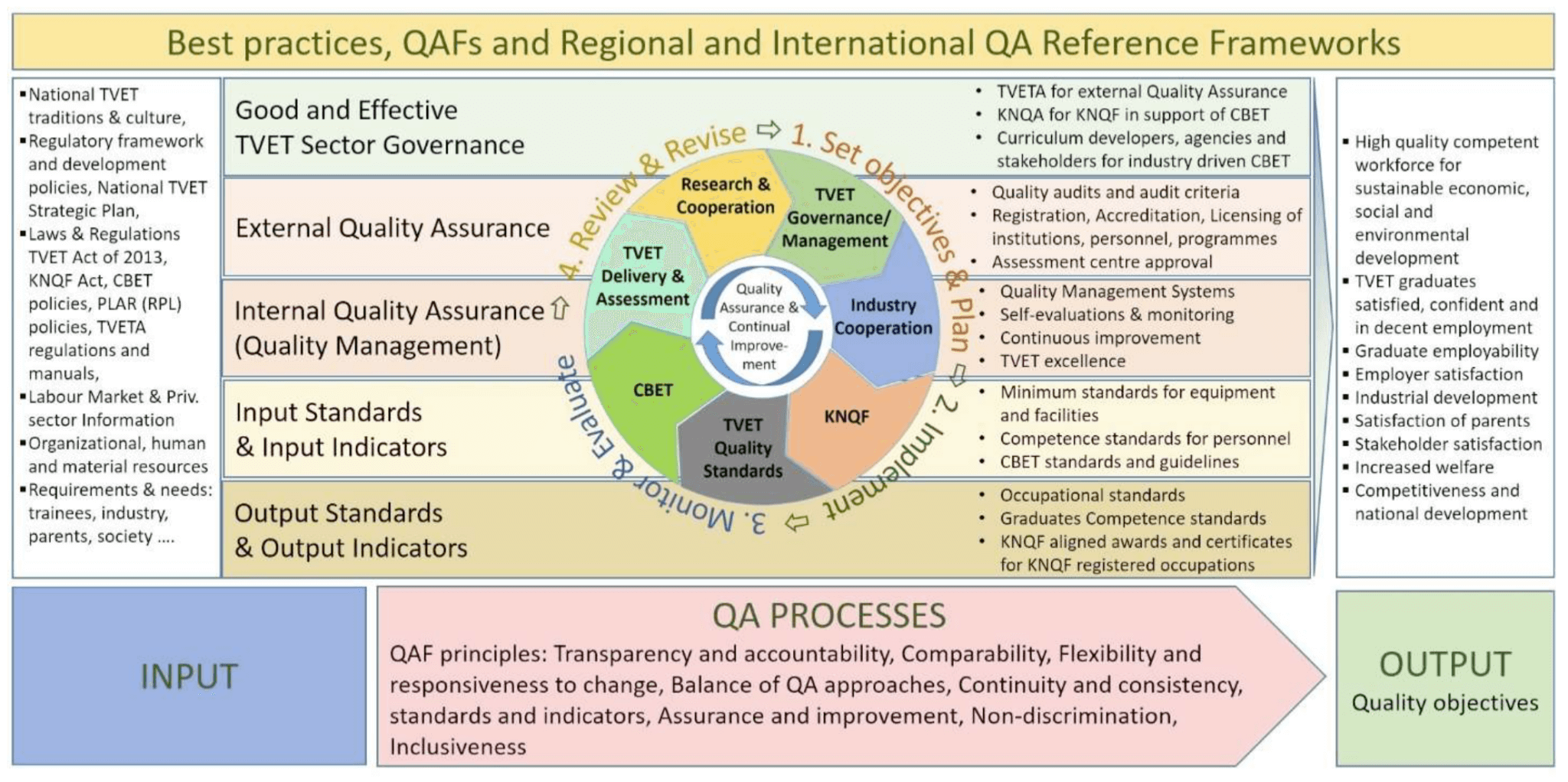

In response to the challenges and demands of citizenry, the Government of Kenya through the Ministry of Education has developed a comprehensive system of TVET quality assurance based on the TVET Act of 2013, the KNQF Act and University Act; No. 42 of 2021, and other subsequent regulations. The lead agency for Accreditation and Registration in the TVET sector is TVETA, the TVET Authority, which has developed the Kenya National TVET Quality Assurance Framework (Figure 1) and whole infrastructure of approaches, methods, guidelines and tools to ensure effective sectoral quality assurance.

The main task of TVETA is to develop and ensure external quality assurance (quality assurance by the regulator or specialised bodies) in a dynamic environment with continuously changing and evolving requirements, thus contributing to the achievement of the overall objective of Kenya’s TVET system of a competent nation. TVET quality relates to the achievement of the outcomes and competences (knowledge, skills and attitudes) as described in the Kenya National Qualifications Framework meeting needs and expectations. External quality assurance, of course, needs to be complemented by the internal quality assurance of all TVET institutions, their quality management.

However, despite its importance, quality in education in general and in TVET specifically is a concept that is not that easy to define and measure. Education quality is an elusive concept and a dynamic idea. It the quality that emerges and realises in the process of delivery and in the process of interaction between the trainer/facilitator and the trainee. Education quality has a two-fold character of technical and emotional aspects, which makes it difficult to define educational quality accurately.

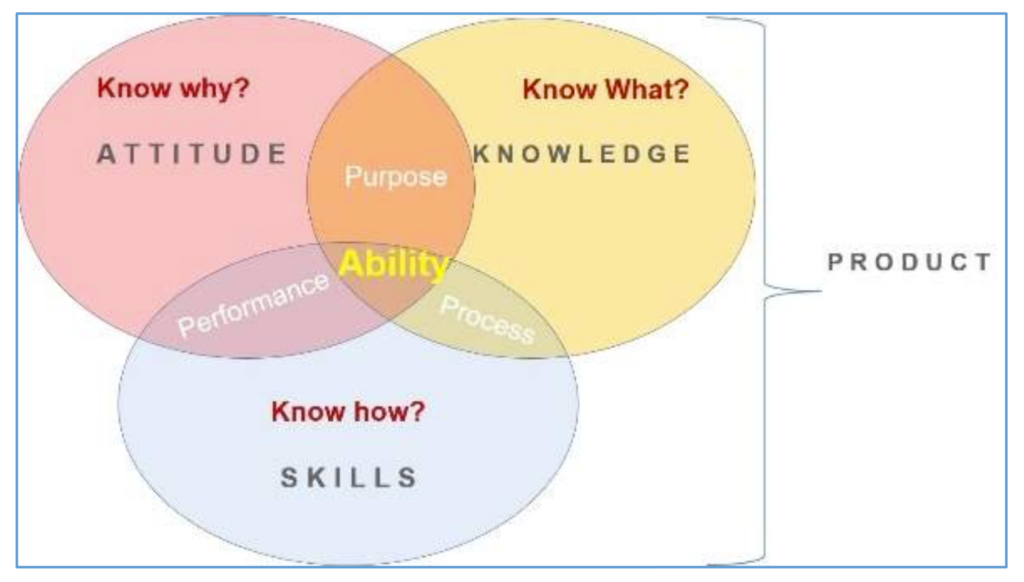

Just taking into account the attitudinal dimensions of competence makes it more complicated to define the competence-based quality concept. Real life is often more complex than theory and academia. People are not technical products, which can be measured through solely their conformity with technical specifications. Additionally, ideas of quality sometimes conflict with one another.

The technical side of quality is best described by the concept of “quality in fact” as the conformity with specifications and standards,3 which is generally the main concept of external quality assurance. The emotional aspect includes the relative notion of quality between bad and excellent, whereby the final decision about the quality of TVET will be measured by the outcomes in terms of successful application of the acquired competences in employment or self-employment of the graduates as shown at the output side of Figure 1.

So, what makes TVET quality so special?

a) There can be no absolute consistency or homogeneity in TVET provision other than within certain boundaries (standards). Unlike a tangible product, education and training services cannot be mended. A poor training cannot be ‘repaired’. Re-training will be needed instead. The standard for the services and its provision should be right every time;

b) Education and training services are intangible. TVET services have to be delivered on time and are ‘utilized’ at the moment of delivery, and this is as important as the specifications of the services. Quality assurance here includes, therefore, 1) process quality and 2) the quality

of TVET ‘ingredients’ involved (trainers, facilities, materials etc.).

c) Audits and inspections are often too late. Close personal interaction, formative assessments,

continuous feedback and evaluation in the delivery process are main means of deciding whether the TVET programme is evolving in the right way or not. Continuous monitoring of measurable quality indicators will also be required;

d) Lastly, it is not a simple task to measure success and quality in TVET. Meaningful performance indicators are those of graduate and employer satisfaction. Intangible soft indicators such as care, usefulness, courtesy, concern, friendliness and helpfulness are often as important to quality as hard and objective performance indicators. Achievements in life and career and employment often show long after the initial training.

Therefore, TVET has to be seen not as a particular procedure, but as the result of the way in which it takes shape as it moves through the entire TVET cycle. Quality assurance in TVET is not a matter of simply fulfilling performance targets or conformity with standards. The idea of a graduate as a standard product does not fit the complexity of the education and training process.

Figure 2 is an attempt of describing the graduate competence with the “Ability Model”. Ability here means the ability of the trainee/graduate to perform according to specific occupational industry standards. The model shows the interconnection of competences, competencies and aptitudes leading to the ability to produce products or services. Quality assurance needs to address all the aspects of individual ability as depicted to the left.

So, let us try to define TVET Quality from a regulator’s and TVET institution’s point of view in a simple way: TVET Quality is a set of characteristics of a TVET programme, through which mandatory standards set by TVETA and other agencies in charge as well as labour market and stakeholder expectations are met.

2. The importance of workplace-based TVET and its place in the TVET QA system

International trends and aspirations as well as the immanent need to meet the demands of the labour and employment markets and industry naturally induce the need for workplace-based learning and cooperation between TVET and industry manifested through industrial attachments, internships and traineeships. This goes, even internationally, into the direction of different national forms of dual TVET systems. The policy makers in Kenya support a strong cooperation between TVET institutions and industry.

The benefits are 1) higher relevance of programs and strong links between institutions and industry leading to better employability of graduates, 2) training of demand driven competences, and 3) better industry and labour market orientation. Trainees during traineeship or industrial attachment will have “learning by doing” in an authentic real-life situation. They will join the normal work flows-processes in the workplace, which include social, technical and emotional skills.

The technical and vocational education and training locations include the TVET institutions as defined in the TVET Act, other educational institutions (e.g. Higher Education) as well as companies and organisations engaged in economic activity, in institutions not engaged in economic activity (public service), in other establishments, such as independent professions (for example lawyers and auditors). This means that any training employers of any size and form able to provide suitable workplace learning can be called a Workplace Learning Provider.

TVET quality can be addressed and managed through the establishment of a quality assurance system, which includes all components of TVET, such as the material basis, the human resources and the programmes, units and curricula as well as the way TVET is delivered, including methodology and real work / life exposure through workplace-based learning (training), in a systematic way. Quality of education can be measured at different levels, including at the level of employer and employee (graduate) or at the level of students and other stakeholders.

In this case the quality of the ‘products’ (graduates and students) is measured. Other aspects as programmes, curricula, materials, trainers, workplaces are means used to educate and train competent graduates. Subsequently, Figure 1 includes “Industry Cooperation” as one of the seven central elements of TVET quality assurance. Such cooperation should cover the entire TVET cycle from the establishment of occupational standards to the assessment.

Cooperation is needed to capture and capitalize on the state-of-the-art developments, technologies used in industry and to provide the trainees with a taste of real work-life from the setting of the training standards to the practical competence training application by the workplace learning provider. This creates a true win-win situation for all stakeholders involved. The TVET institution is able to offer relevant programmes, the workplace learning provider can directly contribute to the quality of potential future employees reducing future costs and the trainee will increase satisfaction and employability. Workplace Learning Providers also contribute to specific TVET programmes in other ways than offering workplace learning, including with guest lectures, excursions, assignments, assessments etc.

On the way to the final verified summative assessment of the trainees, which will lead to a qualification aligned with the Kenya National Qualifications Framework (KNQF), workplace- based learning and training experiences will be an essential part of TVET delivery. The question here is; what competences trainees/graduates are to possess to be successful? The KNQF and occupational standards as well as training standards help to determine those occupational competences (=learning outcomes) and to design and deliver meaningful TVET programmes. The participation of Workplace Learning Providers in this process is crucial.

In this article we look specifically at the part of quality assurance of workplace learning in the process of TVET delivery. The question here is; how to make sure that workplace-based learning is contributing to the successful delivery of a TVET programme and that the best possible outcomes for the trainees are achieved? This is of specific importance looking at the diversity of Workplace Learning Providers, the different industries, pre-conditions of training employers of all sizes and shapes. How to ensure real and meaningful learning quality in all these different settings? How to balance the need for quality assurance and motivation of workplace learning providers?

First of all; this will need a good cooperation between the TVET institution at which a specific programme is mounted and which will take the main responsibility for the quality of the entire programme and the workplace learning provider. Secondly, the quality assurance of workplace learning providers needs to be effective, but not disengaging. Thirdly; workplace learning providers need to be engaged, involved and motivated in the entire process of preparation, delivery and assessment of the workplace-based learning to best consider their requests and needs.

Of course, some of the requirements externally applied to TVET institutions and TVET trainers, cannot simply be applied to the workplace learning providers. Therefore, quality assurance requirements should not place any unnecessary or formalistic barriers to successful institution- industry cooperation. It cannot be expected that the workplace-based trainers and instructors will seek registration and licensing with TVETA. A requirement for licensing in Kenya is among others a pedagogical training, which cannot be expected in industry.

However, some form of quality assurance of workplace-based instructors/coaches/mentors/supervisors should be established and maintained. To capture the challenge of quality assurance in workplace-based TVET we, therefore, suggest guiding quality principles to be applied in close cooperation between TVET institution and workplace learning provider. These guiding principles for quality assurance in workplace- based learning should include:

- The TVET institution bears the overall responsibility for the delivery of the TVET programme. To keep the administrative burden as low as possible for the workplace learning provider, the responsibility to ensure compliance with the requirements for the workplace and the personnel engaged in TVET at the workplace is mainly placed on the TVET institution. The task of the institution is to ensure the quality of workplace learning in a collaborative manner and to document this process for quality assurance purposes. The TVET institution shall ensure that training and workplace learning environments are suitable and that the personnel involved in the workplace learning have the necessary personal and technical competences. There should be, however also some interaction between the regulator, the TVET institutes and the workplace learning providers themselves. This to consistently achieve qualitative workplace learning in case they don’t take responsibility for it. If shortcomings are discovered, the TVET institution shall work to overcome those in a collaborative manner with the workplace learning provider. If workplace learning will not be possible without a danger to health or limb of the trainee, the TVET institution shall not place its trainee at this workplace;

- Guidelines and criteria for 1) workplace learning providers in all forms of settings, 2) workplace/ industry-based instructors and 3) monitoring and evaluation of the workplace- based learning should be established and implemented;

- Quality records and reports should be kept and maintained and reported, including in external institutional quality audits and inspections.

3. Suggested criteria in workplace-based learning4

3.1 Workplace learning provider criteria

The following criteria should be adhered to by TVET institution and workplace learning provider in a collaborative manner. The institution must maintain records proving the suitability of the workplace learning provider with the purposes of the jointly delivered programme. This will, in all situations require a good communication. The draft standard and guidelines for industrial attachment (Chapter 4) introduce the “Industrial Attachment Committee” as a way to facilitate good cooperation and mutual understanding. Ideally, the workplace learning providers would be able to provide tasks meaningful and relevant for the specific TVET programme of the trainees by workplace-based staff who have the required pedagogical and technical skills to do so. It has, however, to be mentioned that a requirement of formal pedagogical training to the staff of the workplace learning providers realistically cannot be applied.

1a) Workplace learning providers shall ensure that the vocational competence necessary for trainees to achieve the purpose of their workplace learning experience is imparted to them. Further, provide workplace learning systematically in line with the intended outcomes. The outcomes should be agreed upon with the TVET institution in accordance with occupational standard -> training standard -> and (CBET) curriculum;

1b) Suitability of premises, equipment and materials of the workplace learning provider;

- Equipment of the training premises and training premises are suitable for the workplace learning.

- Minimum standards for the size, light, equipment, management, health and safety of training premises may apply.

- Ratio between the number of trainees and the size of training space

- Ratio between the number of trainees and the competent staff assigned is appropriate.

1c) Sufficiency of the specified workplace learning period for the purpose of the training;

1d) Assign a competent and suitable instructor (workplace coach, mentor, facilitator) to the trainee;

1e) Provide the trainee with the materials, in particular tools, supplies, and personal protective

equipment necessary for their specific workplace learning and ensure formative (continuous)

and summative (final assessment) as necessary;

1f) Keep written training records as agreed upon with the TVET institution as evidence of the

workplace learning provided;

1g) Ensure that trainees during their workplace learning are protected from mental, physical, moral

and social danger;

1h) The workplace learning schedule shall be harmonised with the training and learning at the

TVET institution according to the TVET programme.

1i) The workplace learning provider should provide the trainee and TVET institution with a

written certificate on his/her workplace learning. The certificate shall be signed by the instructor assigned to the trainee, and if this is not possible, by the responsible manager. The certificate must contain information on nature, duration and purpose of the workplace learning, as well as the competences acquired by the trainee. The certificate shall include particulars of their conduct and performance. The workplace learning provider will provide a recommendation letter.

3.2 Criteria for personnel engaged in workplace learning

2a) Trainees may only be engaged by suitable workplace learning providers (see criteria set 1);

2b)Trainees may only be trained by persons who have the necessary personal and technical competence in relation to the specific workplace learning. Such industry-based instructors’ / workplace coachers must be appointed, who can impart the specific training content;

2c) Under the responsibility of the assigned industry-based instructor, additional persons can take part in the provision of the workplace learning who have the necessary vocational skills, knowledge and qualifications as well as the personal qualifications necessary to impart specific training content;

2d) Personal competence: Persons shall be deemed to not have the necessary personal qualifications if they have committed serious criminal offenses or repeatedly violated their responsibilities in workplace learning;

2e) Technical competence: Persons shall be deemed to have the necessary technical competence, if they possess the vocational competence and qualifications as well as the workplace-based trainer/instructor/mentor/coach skills (to be determined by the TVET institution) to provide the specific workplace learning;

- Passed the final assessment and certification in a technical field corresponding to the specific training, and/ or;

- Passed a recognized assessment or a summative assessment at an accredited TVET institution in the respective technical field, and/ or;

- Passed a final examination at a Kenyan higher education institution in the respective technical field, and/ or;

- Have acquired a recognised occupational competence abroad, and/ or;

- Have been employed in their relevant occupational field of competence for an appropriate

period of time (documentation needed);

2f) If a regulatory requirement, the workplace learning instructor must be registered/licensed with

the relevant registering body in his/her profession;

2g) Industry-based instructors should be interested/have passion in working and nurturing trainees;

2h) The motivation of industry-based instructors should be considered.

3.3 Monitoring and evaluation of workplace-based training

The TVET institution shall ensure that an appropriate monitoring and evaluation procedure is established and continuous communication maintained with the workplace learning provider. The M&E procedure should capture 1) the satisfaction of trainees in workplace learning, 2) the achievement of workplace learning objectives and outcomes, 3) the assessment of the trainees by the workplace learning providers, 4) the subsequent impact of the workplace learning in terms of employability and labour/employment relevant competences, 5) the interaction between assignments and instructions given by the TVET institute and tasks relevant for the workplace learning provider, and 6) challenges and possible solutions.

These M&E measures shall be integrated in the institutional programme evaluation and trainee support functions. An appropriate documentation of the workplace learning M&E shall be maintained.

4. TVET Standard — Industrial Attachment — Requirements and guidelines

TVETA, the lead agency for TVET quality assurance in Kenya, has intensified the process of establishing a national standard for workplace learning, “Industrial Attachment – Requirements and guidelines”. The draft standard was produced in July 2022 and is now open stakeholder discussion before being approved.

The draft standard emphasizes that TVET quality requires strong collaboration between training providers and the industry to ensure trainees get workplace learning opportunities. Such opportunities as obtained through industrial attachment provides a hands-on opportunity to trainees to develop skills in a work-based setting. This draft Standard and Guidelines prescribe requirements to be met by both the workplace learning provider and TVET institutions to ensure that quality industrial attachment is offered to TVET trainees. The use of this Standard and Guidelines is expected to not only create harmony in the conduct of the industrial attachments but will also improve their quality across the Kenyan TVET sector.

The standard and guidelines will provide guidance for the management of industrial attachments and distribute roles and responsibilities in this process for TVET institution, industry, trainees, assessment bodies and regulator. It will include the establishment of a standardised reporting in form of a log book, the roles of industry supervisors, mentors/coaches, Industrial Attachment Committee and will include provisions protecting the interests of the trainees as well as for a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation of industrial attachments.

5. Kenya National Qualifications Authority – Setting the framework for national competence assessment

The Kenya National Qualifications Authority (KNQA) was established in 2015 as set out in the Kenya National Qualifications Framework (KNQF) Act no. 22 of 2014 and KNQF Regulations, 2018 to support coordinate and harmonize the various levels of education; and to produce a database of all qualifications in the country. KNQA being a major sector regulator in TVET was informed by Sessional Paper No. 1 of 2019 (formerly 2012) in setting up a national qualifications framework.

The KNQF is a learning outcome-based qualifications framework, encompassing all educational and training sectors and all forms of learning; formal, non-formal and informal learning. The KNQF embraces of levels, each being recognized by a unique set of Level Descriptors. In order to place a qualification on any KNQF level, the learning outcomes (L.O.) of each unit involving a qualification and the overall qualifications learning outcomes are mapped against these Level Descriptors.

At each level, the Level Descriptors are classified into three separate strands (categories) covering Knowledge, Skills and Competencies. The KNQF is using these categories, whereby the term “competencies” as the source of attitudes replaces the term “attitudes”. Competences in this interpretation are not the same as competencies.

The principles for which the KNQF is established is to promote access to and equity in education, quality and relevance of qualifications, evidence-based competence, and flexibility of access to and affordability of education, training assessment and qualifications. The decision to develop the Kenya National Qualifications Framework was made after several challenges were found to be facing the education system in Kenya. These were inclusive of:

- Globalization and internationalization of Education Systems

- Technological change and educational transformation

- Poor linkages between qualifications and the labour market requirements

- Lack of consistency in qualifications (even among institutions offering same level qualifications)

- Bottlenecks and Dead Ends Education and Training.

- Absence of a system for comparing qualifications to each other

- Pathways of progression between qualifications was unclear and cumbersome

- The Evaluation of Value of qualifications to employers and others users of qualifications

- The learners were unclear with education pathways and the Country had an education system that was not able to address its social-economic and technical challenges appropriately.

6. Conclusions

- In order to nurture African core values and promote sustainable development at the national, sub-regional and continental levels, the African Union Commission developed a comprehensive ten-year Continental Education Strategy (CESA) 2016-2025. Strategic Objective 4(c) of CESA states that there is need to “Set up national qualification frameworks (NQFs) and regional qualification frameworks (RQFs) to facilitate the creation of multiple pathways to acquisition of skills and competencies as well as mobility across the sub-sector”;

- Kenya has developed an effective national framework for TVET quality assurance encouraging cooperation of all TVET stakeholders at all stages of TVET delivery. This framework is aligned with best international practices. Main cornerstones of this framework are the Kenya National TVET Quality Assurance Framework (KNTVET QAF) with the related regulatory framework and the Kenya National Qualifications Framework (KNQF);

- The TVET quality assurance framework in place facilitates quality assurance in workplace- based training in a cooperative, participatory and mutually beneficial way, where quality TVET delivery throughout a TVET programme benefits trainee, TVET institution, workplace learning providers and society.

7. Recommendations

- Quality assurance of workplace-based training needs to be assured in a cooperative manner, whereby the TVET institution, where a programme is mounted, takes a leading, facilitating and coordinating role;

- Regulators (e.g. TVETA), together with the stakeholders, should develop the necessary guidelines and criteria for workplace learning providers as complementing tools to the TVET QA framework making sure that this field of cooperation will not unnecessarily be overregulated or too costly for the workplace learning provider. TVETA has started to do so by drafting the Industrial Attachment Standard and Guidelines mentioned under chapter 4. The guidelines and criteria need to be tailored to the needs and conditions of workplace learning provision;

- The main objective of quality assurance in workplace learning (attachments, traineeships, apprenticeships, internships) should be about how to ensure that workplace-based learning is contributing to the successful delivery of quality TVET programmes and that the best possible outcomes for the trainees, institutions and workplace learning providers are achieved.

Footnotes

1 Dr. John Osoro is Deputy Director of the Kenya National Qualifications Authority (KNQA), Republic of Kenya; Andreas Reinsch is an international education consultant, trainer and researcher currently working as Quality Assurance and Partnership Expert for Cadena – International Development Projects, with the TVET Authority of Kenya under the Nuffic Orange Knowledge Program

2 Competence includes the necessary knowledge, skills and attitudes to perform in line with industry standards. The reader should keep in mind that the term competences is often used inconsistently in different TVET systems around the world and often used synonymously with the term “Competency”, which could be regarded as incorrect. The Kenya National Qualifications Framework (KNQF) uses the classification Knowledge, Skills and Competence for the level descriptors, where the term competence is replacing the term attitudes. This might contribute to confusion, if not critically applied.

3 Quality in fact is the basis of the quality assurance systems as applied by the international certification standard for quality management systems ISO 9000 – Requirements for Quality Management Systems

4 The wheel does not need to be reinvented here. The German Vocational Training Act 2005, which was reviewed for this part, provides suitable sets of such criteria.

References

- Vocational Training Act, Germany, (2005)

- Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology, (2012), Technical and Vocational

Education and Training (TVET) Policy, Government printers, Nairobi, Kenya, John Nyerere, (2009), Technical & Vocational Education and Training Sector in Kenya, For the Schokland, TVET program, Nairobi, Kenya - Ministry of Education, (2021) National TVET Blueprint, Government print, Nairobi, Kenya

- Ministry of Education, (2013), The Technical and Vocational Education and Training Act,

Government printers, Nairobi, Kenya - Ministry of Education, (2014), The Kenya National Qualifications Act, Government printers,

Nairobi, Kenya

Very educative to me and my institution as a whole. As IQAO , I do encourage quality in the services we offer . Share with more materials on TVET – Quality Assurance. Thank you

insightful article, kindly share with the Quality assurance of the assessments in the TVET sector