Memory Matsikure1, Chisiri Benard2, Machaka Tafadzwa.H.T.3, Mutumwa Allen4, Nyakuamba Takesure5, Chikozho Martin6, Muchongwe Nevermind7, Kwembeya Maurice8, Shumba Godwin9

1, 2, 3, 4, 5,6,7,8, 9 Manicaland State University of Applied Sciences, P. Bag 7001, Mutare, Zimbabwe

Abstract

This research study sought to explore inclusive practices that could be incorporated at Technical Vocational and Educational Training (TVET) institutions in Zimbabwe. The study employed a qualitative research methodology using a multiple case study design and thematic data analysis technique. Purposive sampling technique was used to select participants from each category of the population under study. Participants comprised of Heads of Departments (HoDs), lecturers and students from three TVET institutions from Mutare, Zimbabwe. Data collection techniques used comprised of focus group discussions with a total of 28 students and interviews for 8 HoDs and 15 lecturers respectively.

Research major findings were: TVET institutions are facing challenges in effectively supporting students with diverse needs; some TVET curriculum does not carter for various student diverse needs; efforts are being made towards putting in place more inclusive setup in TVET institutions in Zimbabwe but challenges are being experienced; students with impairments are not accessing specific training facilities basing on their needs; Attitudinal inclinations have also contributed to the plethora of challenges faced by vulnerable students particularly those living with disabilities, socioeconomically disadvantaged, those living with HIV/AIDS and also females and males.

Research results also revealed that only one out of the three TVET institutions under study offer students support in form of fees, uniforms, stationery, sexual reproductive health rights education, child care services for children of mothers pursuing their technical and vocational education. Results imply the need for more to be done for inclusive vocational and technical education in Zimbabwean TVET institutions to be effectively achieved.

Key Words:

integrating, inclusive TVET, vocational and technical, education, Zimbabwe, training institutions

Introduction/ Background

Inclusive vocational and technical education refers to a system that meets the needs of all learners regardless of their social background, gender, level of achievement, ethnicity, disability, age, migration status and so on (UNESCO, 2019). Hence, incorporating inclusive vocational and technical education in Zimbabwe TVET institutions would entail creating an environment enabling all learners with their diverse needs attain technical and vocational education.

Education in Technical and Vocational Education Training (TVET) institutions in Zimbabwe like other low income countries have undergone immerse model modification since independence in 1980. One of the major thrusts being working towards the integration of inclusive practices in these institutions. Hence, the country has responded to important international inclusive education frameworks (Mtepfa, et al., 2007). Learners from diverse backgrounds including those living with disability, living in extreme poverty, females, people living with HIV/AIDS and ethnic minorities have limited access and support to vocational and technical education despite the availability of policy and legislation promoting inclusivity in the Education sector.

The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals include a target of ensuring equal access to vocational training at all levels for vulnerable persons (Target 4.5), (International Labour Organisation (ILO), 2017). TVET institutions are vital in the development of nations globally. Considering the challenges affecting economies, societies and environment due to factors such as climate change, digitalization, novel entrepreneurship practices and emerging global pandemics, this research effort therefore, sought to establish how inclusive practices could be incorporated at TVET institutions in Zimbabwe headed for producing tangible solutions towards vision 2030.

Malle et al. (2015a) found that vulnerable students including those living with disabilities participating in vocational education and training programmes reported facing universal obstructions compared to their non- vulnerable counterparts. However, Zimbabwe like other countries has laws and framework upholding the rights of people living with disabilities namely: Constitution of Zimbabwe (2013) guarantees equal rights to all people and provides for inclusive education at all levels of the education system.; Education Act of 1996 accentuating the right to education for all regardless of one’s differences; Disabled Persons Act [Chapter 17:01], and the National Disability policy (2021).

There are also international laws and conventions such as the UNESCO 1989 Convention on Technical and Vocational Education which guarantees equal right of each person to vocational and technical training and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) to all people and provides for inclusive education at all levels of the education system. TVET is education that prepares individuals for specific trades, crafts and careers at various levels in the world of work and entrepreneurship development (UNESCO, 2015).

Jabbari (2015) argues that the goal of education is not merely giving information to learners by facilitators but rather about giving practical skills to learners which should be noticed during training. UNESCO (2014) ruminates the following features as essential for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET);

(a) an integral part of general education

(b) a means of preparing for occupational fields and for effective participation in the world of work (c) an aspect of lifelong learning and a preparation for responsible citizenship, and

(d)a method of facilitating poverty alleviation.

Although it is a legislative mandate to accommodate students with diverse needs in all the institutions of higher learning, research shows that there are still some barriers in fulfilling this transformation agenda (Mosia & Pasha, 2017).Furthermore, acquiring vocational and technical education is the key to decent employment, yet there are some obstacles which increase the risk of exclusion of vulnerable persons (UNESCO, 2019). Barriers to learners from developing countries’ access to inclusive vocational and technical education include: limited resources, poverty, lack of industry experience for lecturers, lack of transfer across streams in the education system, and weak participation from stakeholders (Norton & Norton, 2023).

Effective vocational skills training is seen as an essential prerequisite for the creation of a productive workforce that has the potential to contribute significantly to the socio-economic development of a country (Malle, 2016). However, Africa has a large number of young people who do not have access to education that affords them skills needed for employment (AU, 2007). Moreover, benefits of technical/vocational education include: easy job employment, offering careers in hands-on fields, increase in quality life and removal of barriers (Norton & Norton 2021). Therefore, mainstreaming vocational and technical education helps to create a mutual bond between learners that promotes recognition of diversity and overcome barriers to learning and participation for all people.

Most studies carried out on inclusive vocational and technical education mostly considered inclusive education for a specific group of vulnerable learners living with disabilities without focusing much on information seeking concerning with regard to learners with other diverse learning needs. Hence, the current research seek to close this gap by investigating on incorporating vocational and technical inclusive education in TVET institution considering needs of learners with diverse learning needs.

The research study sought to answer the following questions: (i) what are the diverse learning needs of learners at TVET institutions? , (ii) which barriers hinder incorporation of inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions? , (iii) which are the measures and practices for incorporating inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions?

Method

To discern the practices that could be incorporated in promoting inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions, this research study employed a qualitative research methodology using the multi case study design. The qualitative methodology allowed for the undiluted account of the phenomenon under study by taking into consideration the participants’ social context (Kim et al., 2017). Qualitative research methodology gave the researchers the opportunity to study participants in their natural environment and provided a means for collecting and analyzing information based on participants’ views and the way they understood their setting (Creswell, 2014).

Multiple case study research design which involves selection of several cases to further understand a phenomenon, population or general condition (Creswell, 2012). For this study, a collective study of three TVET institutions in Mutare district of Zimbabwe was combined in a single study. Multiple case study was adopted due to the fact that studying more than one TVET institutions may have considerable analytic benefits and conclusions more powerful than those from a single case study.

Participants

Participants were drawn from three TVET institutions of Mutare, Zimbabwe. Purposive sampling technique was used to select 28 students, 8 HoDs and 15 lecturers. Purposive sampling was employed due to its suitability to select distinct cases that are particularly informative (Neuman, 2014). Therefore, participants were selected on the basis of them likely to be knowledgeable concerning incorporation of inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions. Such participants were selected on the basis of particular characteristics within their respective functions.

The purposive sampling strategy used was maximum variation (heterogeneous) to maximize a diverse range of cases relevant to the current study (Emmel, 2013). The purpose of maximum variation was to document diverse variation and identify important common patterns (Creswell, 2014). Students, lecturers and HoDs were selected from the population as they were representative and informative on the measures in place for incorporating inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions in Zimbabwe. Participants, inclusive of students, HoDs and lecturers’ age ranged between 19 and 61 years.

Data Collection Tools

Data collection tools used were: the semi structured interview to solicit data from HoDs and lecturers and a focus group discussion guide to obtain data from students. Interviews were conducted to obtain data from participants on a one on one basis. The interviews accorded the participants with the opportunity to opinions, views, and comments on incorporation of inclusive vocational and technical education. The outline of the interview protocol addressed main aspects of questions the study research aimed to answer.

The focus group discussions provided researchers the opportunity to find out the views, opinions and perceptions of participants in relation to the incorporation of inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions. All agreed opinions, notions and commentaries arising from the focus group discussions were noted on a chart. The focus group discussions were researcher directed and lasted for 40 minutes. The interviews lasted between 20 to 25 minutes each.

Data Collection Procedure

Identification of participants who could best provide informative information answering the study research questions was facilitated through the help of the institutions under study’s administrators during recruitment phase. During enrollment phase, participants exposed to informed consent information and afterwards engaged in focus group discussions and interviews. The focus group discussions were conducted at the institutions under study. Interviews were conducted face to face, over the phone and WhatsApp call platforms depending on the interviewees’ availability circumstances. Both focus group discussions and interviews were voice recorded. Participants were allowed to respond in a language of their choice. Recorded data were then transcribed from vernacular language to English were applicable.

Ethical Considerations

Researchers obtained ethical clearance from Manicaland State University of Applied Sciences research. Permission to collect data was granted by the responsible authorities for the TVET institutions under study. Briefing was done with participants to explain the nature, purpose, objectives of the study and detailed information was given by researchers to the participants. The participants were accorded the chance to give consent before participating by signing the consent forms provided. The participants were also informed of their right to withdraw from the research study anytime without fear of victimization and were assured of privacy and confidentiality during data reporting, analysis and publication. Participants were informed that there was no potential harm either physical or psychological and were not forced to answer questions that might may make them feel uncomfortable.

Data Analysis

Thematic data analysis by Braun & Clarke (2006) was used. This data analysis method enabled the researchers to code and categorise data into themes. The data analysis stages included: familiarization with the data; generating the initial codes; sorting and collating all potentially relevant coded data extracts into themes; reviewing coded data extracts to determine appearance in coherence pattern; and refining of themes through detailed analysis. The themes facilitated the understanding, inference, and enlightenment on participants’ perceptions through definition of concepts, mapping, creating typologies, finding associations, providing explanations and developing strategies towards improving the incorporation of vocational and technical education in TVET institutions (Byrne, 2022). Four themes emerged from the thematic data analysis process.

Results

Themes which emerged from the study were: Understanding of inclusive education; Diverse learning needs of learners at TVET institutions; Barriers hindering incorporation of inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions; Measures and practices for incorporating inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions

Understanding of Inclusive Education

Participants revealed varied understanding of inclusive education and explained the concept in different ways.

Some participants were unfamiliar or unsure with the concept inclusive education and gave general explanations on what they thought it was about. The statements below show the participants’ perceptions on inclusive education:

”I am not really sure. I guess this includes all learners learning in the same environment including those living with disabilities”.(Student from institution C Focus group discussion)

“I have never thought much about this concept before so I am not really sure how to define the concept. But, I think it has something to do with upholding learners’ right to education”.(HoD 3)

Other participants defined the term in terms of their personal experience. This notion is supported by statements from participants below:

“Inclusive education involves us teaching learners in the same lecture room so that none of them is left behind irrespective of their disability or other factors, so everyone gets included in the learning process.” (Lecturer 3)

“Inclusive education refers to whereby we work towards upholding the right of all learners to access and obtain an education”. (HoD 1)

However, others understood what it was and could give brief explanations on the concept of inclusive education. Quotations by participants below reveal this fact:

“When the education does not discriminate or segregate against learners considering their circumstances”. (Student from institution A focus group discussion)

“I think this is whereby the curriculum carters for all learners regardless of their background”. (Lecturer 2)

Diverse Learning Needs of Learners at TVET Institutions

Participants indicated diverse learning needs of learners at TVET institutions. There are various categories of TVET institutions learning needs for learners as mentioned by participants.

Some learners pointed out that one category of learners at TVET institutions was that of learners living with disabilities. The following statements from participants support this notion:

“We also enroll learners living with disabilities especially intellectually and physically handicapped with moderate conditions”. (HoD 5)

Another category of learners in TVET institutions mentioned by participants was learners from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds as well those advantaged. The following quotations reveal this fact:

“Some learners at this institution are from poor backgrounds and it is difficult for them to pay their fees on time and can hardly afford some of the requirements in terms of learning materials and e-learning gadgets, protective clothing such as work suits, safety shoes and so on”. (Participant from Institution A student Focus group discussion)

Learners living with HIV/AIDS is another group of diverse learners found at TVET institutions as specified by participants from the following statement:

“There are also learners living with HIV/AIDS at this institution. They also get support from the institution’s health department for their medication and regular checkups. However, some learners do not openly seek such services for fear of discrimination and segregation.” (Lecturer 8)

There was an indication also of learners who have not been successful in schools. However, participants specified that even those who were successful in school have their distinct needs. The following statement form a participant’s quotation below reveals this view:

“Learners who do not have 5 O levels tend to need more time and attention than those who were successful in their national high school examinations. Hence, when teaching learners from both camps, one has to carter for both groups and make sure their learning takes place effectively”. (Lecturer 10)

Participants identified one category of females as well as males as having diverse learning needs. The statement from a participant below shows this notion:

“Females learners have their own learning needs considering that some come for vocational and technical training whilst they are mothers or wives. Some males also attend vocational and technical education being family men. Hence, responsibilities might affect such females and males as they endeavour to acquire a TVET qualification”. (Student from Institution B focus group discussion)

Minority groups such as refugees and learners from neighbouring countries were indicated by participants as having their own learning needs as shown in the quotation below:

“Learners from other countries and refugees are also part of the studentship of our TVET institution and these normally face challenges of culture integration and language barrier which hinder their effective learning. Hence, some end up dropping out without completing their courses.” (HoD 4)

Barriers hindering incorporation of inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions

Participants indicated that there are numerous barriers hindering incorporation of inclusive and technical education in TVET institutions. The following statement from a participant reveals this fact:

“Even though inclusive education is a contemporary issue in TVET institutions, implementation is proving to be a challenge to various barriers or obstacles.” (HoD 7)

Infrastructure factor was mentioned by several participants as one barrier to inclusive vocational and technical education. Participants indicated the following:

“We do not have infrastructure appropriate for some learners with diverse needs especially those with physical disabilities who use wheel chairs due to the unavailability of ramps or lifts in our institution building. Even the administration block is not accessible to wheel chair users due to that fact and hence we are only able to enroll learners with mild to moderate Physical disabilities. Such as those who use crutches or walking sticks”. (HoD 8)

“Lecture rooms are up stairs and therefore not disability-friendly and hence not accessible to learners who cannot use the stairs and need to use ramps or lifts. Even braille material or computers that can do braille work are not available”. (Student from Institution A focus group discussion)

“Among other factors, there are no electric books for the visually impaired students. Moreover some rooms have poor lighting and noisy rooms with large group sizes and lecture rooms layout are unfavourable which makes moving around difficult. Wi-Fi is poor and some of us cannot afford to buy the expensive mobile data bundles”. (Student from Institution A focus group discussion)

Participants specified lack of lecturer skills and training for lecturers as one of the barriers to inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions. The following statements show the participants’ views:

“Since I started teaching at this institution, I have never attended any in-service training workshops or courses.” (Lecturer 12)

“Lecturers may identify students with diverse needs but mostly do not know how to cater for their needs due to lack of training or skills to deal with such learners. We have plans to train them but nothing has been put in place yet due to unavailability of funds.” (HoD 5)

“The institution has only one counselor and considering our enrollment he cannot provide service to learners with diverse needs. More qualified personnel to deal with these learners are needed”. (Lecturer 9)

Another barrier for inclusive vocational and technical education mentioned by participants is inadequate funds for infrastructure, materials, staff training and retention and families for learners with diverse learning needs. The following statements by participants reveal this notion:

“A lot needs to be done in terms of promoting inclusive vocational and technical education but our hands are tied. There are no funds for renovating our buildings to accommodate learners with diverse needs and even to acquire learning materials needed even for training lecturers and other staff in accordance with the diverse needs of learners attending TVET institutions”. (HoD, 2)

Rigid curriculum teaching methods is another barrier for inclusive vocational and technical education indicated by participants. Some lecturers indicated doubt in the effectiveness of the methods they use whereas some students felt that the teaching methods were not suitable for their situation whereas others felt they were not adequately addressing their learning needs. Participants indicated that:

“I am not sure if I am doing it right when teaching. I just teach all students using the same methods because I was never trained to teach learners with diverse needs”. (Lecturer 10)

“The lecturers are usually too fast for us to understand when explaining concepts such that I have to ask my colleagues for help after lectures”. (Student from Institution C focus group discussion)

It seems lecturers are not ready to make modifications and accommodations to their teaching methods for example by limiting written work for learners who cannot write fast because same teaching objects may be achieved through different methods.

Attitudinal inclinations were mentioned as one of the barriers to inclusive vocational and technical education as evidenced by the following quotation from a participant:

“Society and most education systems have a tendency of treating learners with diverse learning needs differently. This attitude which is negative make it difficult for such learner to fit in the vocational and technical education institutions”. (Student from Institution B focus group discussion)

Measures and Practices for incorporating inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions

Participants indicated various measures and practices for incorporating inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions.

Inclusive education policy implementation was mentioned by several participants as one measure and practice that would ensure effective incorporation of inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions. The following statements from participants reveal this fact:

“There seem to be no pronounced inclusive policy from the Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education besides the national policies because I have never been encountered one since started teaching in a TVET institution. Hence, the need for a well-defined ministry based policy and the funding for effective implementation”. (Lecturer 4)

Inclusive flexible curriculum and enrollment process were specified to be another measure to promote incorporation of inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions. One participant had this to say:

“It is imperative to do away with rigid curriculum and the enrollment procedures so as to accommodate learners with diverse learning needs. Curriculum should be flexible in terms of subjects, language of instruction and assessment procedures to meet the learning needs of diverse students”.(Lecturer 7)

“There is need for agility in the balance between assessed course work and examinations and demonstration of achievement in other ways, such as through signed presentations or viva voice examinations”. (Lecturer 13)

Modification and accommodation of Instructional methods was suggested as a measure and practice that promotes incorporation of inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions.

“Lecturers should do away with traditional instructional methods and adopt more inclusive teaching methods which carter for learners with diverse learning needs”. (Student from Institution B focus group discussion)

Creating institution environment and infrastructure conducive for inclusive education was suggested to be another measure and practice promoting inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions. This is evidenced by statements from participants below:

“Ramps, lifts, amenities and affordable tuition, lecture rooms and additional rooms for learners who need alternative arrangement during exam time is another favourable way to incorporate inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions”. (HoD 6)

“If specialist equipment allowance is allocated to a student per course for all full and part time students this would go a long way in promoting incorporation of inclusive vocational and technical education”. (Student from Institution C focus group discussion)

Participants reported that TVET institutions should offer supportive services and resources. Current research findings indicate that there are limited supportive services and resources for learners of diverse needs. The following quotations from a participants reveal these notions:

“There is a play center which makes it possible for mothers or fathers who want to pursue their vocational and technical training to be able to do so whilst their children at the play center”. (Student from Institution A focus group discussion)

“Learners who cannot afford school fees are helped with fees, we all put on uniforms so that we all look the same. Also, we receive sexual and reproductive health education which help us to make informed life related decisions”. (Student from Institution A focus group discussion)

“We sometimes enroll learners with intellectual disabilities and they are able to attain their education here because we have one our staff with a PHD in Psychology”. (HoD 3)

However, the services indicated by participants above are not being offered in all TVET institutions and where they are offered they are limited due to financial constrains which implies the need for intensification if inclusive vocational and technical education is to be maximally realised.

Discussion

Research findings reveal that the concept of inclusive education is understood from varied perspectives. This shows that there is lack of adequate knowledge on what really constitutes inclusive education. Nevertheless, inclusive education from a global perception is broadly considered as change that supports and embraces diversity in the education environment (UNESCO, 2001).

Diversity in education refers not only to disability but acknowledges and respects differences in learners due to age, gender, ethnicity, language, social class, HIV or other conditions. Inclusive education involves strengthening capacity of the education system to reach out to all learners and is a key strategy to understand “Education for all” (UNESCO, 2009).

Research outcomes also show that diverse learners in TVET institutions in Zimbabwe include: learners living with disabilities, socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds as well those advantaged, learners living with HIV/AIDS, learners who have not been successful in schools, minority groups, and one category of females as well as males. This finding concurs with the study conducted by (Possi & Milinga,2017)youths and adults are enrolled, actively participate and achieve in regular schools and other educational programmes regardless of their diverse backgrounds and abilities, without discrimination, through minimization of barriers and maximisation of resources in TVET institutions.

Emanating from the research findings is the fact there are a handful of barriers to inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions. The challenge of insufficient and inaccessible infrastructure is a key barrier to inclusive vocational and technical education hindering learners with special needs from enrolling with TVET institutions. This finding is in line with Delubom et al., (2020) who observed that infrastructure was not disability-friendly. In another study physical access into institutions was found to be a challenge (Mutanga, 2017). Furthermore, Buthelezi (2014) conducted a study on challenges on inclusive education at a TVET college in KwaZulu-Natal and found that students with physical disabilities experienced accessibility constraints to reach the library, lecture halls, and parking spaces.

The revelation that specified lack of, experts, lecturer skills and training for lecturers as one of the barriers to inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions is another drawback. This is similar to findings a study by Delubom et al., (2020) who found that some lecturers did not have a relevant teaching qualification and another study by Nkalane (2018) who found that some lecturers did not have professional qualifications in education but were experts in the banking sector. The current study unearthed that it was difficult for lecturers without knowledge on teaching learners of diverse learning needs to effectively execute their teaching where such learners are involved.

Inadequate funds for infrastructure, materials, staff training and retention and families for learners with diverse learning needs is another key finding of the current research. TVET institutions are therefore, not able to effectively implement an inclusive education policy framework due to lack of funding, resources and lecturers qualified in special needs education. This finding is in line with one from the study which established that chronic lack of funding is a challenge in many colleges which hinders the normal level of their development of TVET institutions (Delubom et al., 2020). Moreover, lack of funding affected the students in many ways, including not affording to pay for their transport fares. In addition inadequate funding also led to lack of equipment, aides, therapy staff and interpreters.

Another key finding from this study is the notion that rigid curriculum teaching methods is another barrier for inclusive vocational and technical education. This is similar to a finding from a study by Chataika (2007) who found that rigid curriculum in Zimbabwean Institutions leads to learners with diverse needs not adequately catered for thereby affecting the implementation of inclusive education. Therefore, this calls for lecturers to make modifications and accommodations to instructional methods so as to carter for inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions.

Attitudinal inclinations were mentioned as one of the barriers. The students with disabilities at the TVET attributed this to a lack of knowledge about and sensitivity to disability issues on the part of some students and lectures. This made it difficult for them to access educational services equally. According to Tugli (2013) Failure to safeguard access to inclusive education is not only a violation of human rights, but also intensifies the burden on families and incurs economic, social, and welfare costs.

The current research findings indicated inclusive education policy implementation measures and practices for incorporating inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions.

Arising from the current research findings was the suggestion that training of lecturers on inclusivity will go a long way in promoting inclusive vocational and technical training. This is in line with another study which established thatthe training offered to lecturers is one of the important factors that can enhance the quality of education that is provided to students (Carew et al. 2019). Since, lack of training for lecturer has a negative impact on the incorporation of inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions, training of lecturers will facilitate effective implementation of inclusive TVET education programmes.

One key finding emphasizes inclusive flexible curriculum and enrollment process. Adjustments and adaptations should be made in the curriculum in order to suit the needs of learners with diverse needs. This therefore calls for the modification and accommodation of instructional as a measure and practice for incorporating inclusive vocational and technical education in TVET institutions.

Creating institution environment and infrastructure conducive for inclusive education was suggested to be another measure and practice. This concurs with a finding from a research by which found out that Infrastructure improvements, purchase and installation of adapted technology and software in the libraries and labs, provision of assistive devices, and employment of disability support officials is essential for inclusive vocational and technical training (Chiwandire, 2019).

Findings also revealed that TVET institutions should offer supportive services and resources. This can be achieved by a multisectoral approach involving all stakeholders in the designing and implementation of inclusive vocational and technical training.

Conclusion

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agenda 2030 of leaving no one behind advocates for the incorporation and inclusion of all people including students in TVET institutions with diverse needs especially those living with disabilities in all educational programmes. This study attests that TVET institutions are anticipated to offer inclusive educational programmes but are experiencing challenges in meeting these demands. In addition, there is still a lot to be done in TVET institutions to incorporate inclusive education to support all learners with their diverse needs and backgrounds in order to achieve the nation’s vision 2030: “Towards a Prosperous and Empowered Upper Middle Income Society by 2030”.

Learners especially from vulnerable diverse groups cannot be accommodated in some TVET institutions because of lack of enabling learning environments in line with their learning needs. There is therefore, need to mainstream TVET education in most institutions and make it accessible to all students with their diverse learning needs. However, some other vulnerable students’ learning needs are being catered for in the current TVET institutions programmes though to a limited extent in form of a few ramps, a few lecturers for students with special needs, play centres for children of mothers pursuing vocational technical education, sexual reproductive rights education and limited fees grants for learners from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Recommendations

- A steadfast all stakeholders attitude that support inclusivity of vocational training education in TVET institutions.

- Engagement of lecturers and trainers directly involved in the training in TVET policy formulation.

- Extend interventions and programmes for technical and vocational education training institutions so as to incorporate inclusive education in producing tangible solutions towards vision 2030.

- The ratified and enacted national and international policies on inclusive education should be implemented.

- Lecturer training and curriculum should be tailored in such a way that will enable the TVET institutions to support learners with diverse learning needs.

- Students from diverse backgrounds including those living with disabilities should be included in the planning of TVET institutions programmes.

- Expanding access to TVET and skills development opportunities for marginalized groups, such as persons living with disabilities.

- Stakeholders, that is the users, the providers and governance should be invigorated to contribute towards meaningful inclusive practices.

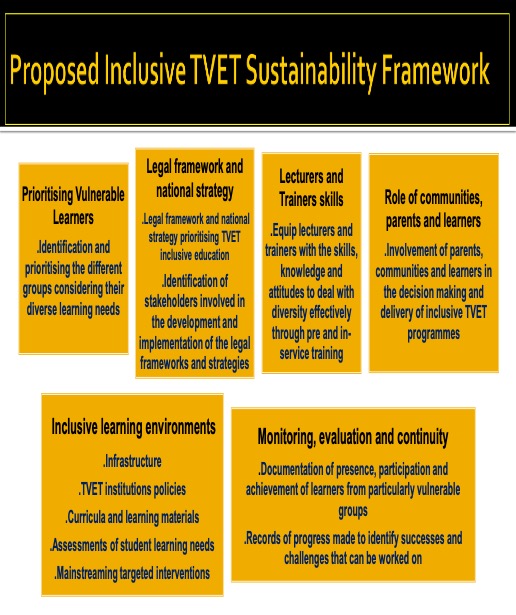

- The proposed sustainability framework developed based on the current research findings below is also recommended to promote inclusive education in TVET institutions

References

African Union (2014). Outlook Report on Education

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buthelezi, M. M. (2014). Exploring challenges experienced by physically challenged students at a Further Education and Training College in KwaZulu-Natal Province. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. University of South Africa, Pretoria.

Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 56, 1391–1412. doi: 10.1007/s11135-02101182-y

Chataika, T. (2007). Inclusion of Disabled Students in Higher Education in Zimbabwe: From Idealism to Reality-A Social Ecosystem Perspective. Doctoral dissertation, University of Sheffield.

Chiwandire, D. (2019). Universal Design for Learning and Disability Inclusion in South African Higher Education. Alternation [Special Edition], 27, 6 – 36. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339202835

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative,Quantitative and Mixed Method Approaches, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Delubom Nosiphiwo Ethel, Marongwe Newlin & Buka Andrea Mqondiso (2020). Managers’ challenges on implementing inclusive education: Technical Vocational Education and Training Colleges. Cypriot Journal of Educational Science. 15(6), 1508-1518. https://un-pub.eu/ojs/index.php/cjes/article/view/5294

International Labour Organisation (ILO). (September, 2017). Making TVET and skills systems inclusive of persons with disabilities.

Jabbari, L. (2015). The Study of Technical and Vocational education and Training. Needs of Dairy and Cooking Oil Producing Companies in Teheran Province. Journal of Education and Practice,6 (10), 97-102. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1081683.pdf

Kim, H., Sefcik, J. S., & Bradway, C. (2017). Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A systematic review. Research in Nursing & Health, 40(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21768

Malle, Y. A., Pirttimaa, R., & Saloviita, T. (2015a). Inclusion of Students with Disabilities in Formal Vocational Education Programs in Ethiopia. International Journal of Special Education, 30(2), 1-10. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/

Malle, A. Y. (2016). Inclusiveness in the Vocational Education Policy and Legal Frameworks of Kenya and Tanzania. Journal of Education and Learning, 5 (4). http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jel.v5n4p53

Mosia, P. A., & Phasha, N. (2017). Access to curriculum for students with disabilities at higher education institutions: How does the National University of Lesotho fare? African Journal of Disability, 6(0), 257. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316547327

Mtepfa, M. M., Mpofu, E.,& Chataika, T. (2007). Inclusive education in Zimbabwe: policy, curriculum, practice, family, and teacher education issues. Journal of the International Association for Childhood Education. International: International Focus, 83(6), 342-346. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/MagenMutepfa/publication/241724361

Mutanga, O. (2017). Students with disabilities’ experience in South African Higher Education – a synthesis of literature. South African Journal of Higher Education, 31(1), 135 – 154. https://www.journals.ac.za/index.php/sajhe/article/view/1596

Nkalane, P. K. (2018). Inclusive Assessment Practices in Vocational Education: A Case of a Technical Vocational Education and Training College. The International Journal of Diversity in Education, 17(4), 1-16. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323373995

Norton, T. & Norton, M. (2021). Top 6 Benefits of Vocational and Technical Education for High School students. TVET Journal.

Norton, T. & Norton, M. (2023). 9 Challenges to TVET in Developing Countries. TVET Journal.

Neuman, W. (2014). Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Pearson.

Possi, M.K. &Milinga, J.R. (2017). Learner Diversity in Inclusive Classrooms: The Interplay of Language of Instruction, Gender and Disability. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 5 (3), 28-45. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1150435.pdf

UNESC. (2001). The open file on inclusive education.

UNESCO. (2009). Sub-Education Policy Review Report: Inclusive Education.

UNESCO. (2019). Virtual conference on inclusive TVET.

UNESCO (2021). Technical and vocational education and training for disadvantaged youths. UNEVOC-TVET.

UNESCO (2016). Orienting Technical and Vocational Education and Training for Sustainable Development. A Discussion Paper. Bonn, UNESCO. http://www.unevoc.unesco.org/publications/

UNICEF (2014). Legislation and Policies for Inclusive Education. New York. UNICEF.

Tugli, A. K., Zungu, L. I., Goon, D. T., & Anyanwu, F. C. (2013). Perceptions of students with disabilities concerning access and support in the learning environment of a rural-based university. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, (Supplement 1:2), 356‒364. https://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/13447/