By Eric Clem Groves and Guliano Bryce

Abstract

Ceremonially opened on the 14th of February 1984, the National University of Samoa was quickly seen as the pinnacle of post-secondary education and training (PSET) in Samoa. By the early 1990s, the Government of Samoa adopted a policy to centralise all its PSET institutions.

This centralisation first commenced with the Western Samoa Teachers College coming under the umbrella of the University to form the Faculty of Education in 1997, which eventually led to the merger of the two remaining largest state funded PSET providers in the country – the National University of Samoa, a provider of higher education and the Samoa Polytechnic, a provider of technical vocational education and training (TVET). Both institutions formally amalgamated through the National University of Samoa Act 2006.

Since, the University has undergone multiple restructures and policy changes in its efforts to improve the balance and delivery between higher education and TVET. The merger of the two institutions came into dispute in 2017 when the Government of Samoa strongly considered the disaffiliation of the former Samoa Polytechnic from the University due to contentions that the University’s systems and structure favoured its higher education programs in terms of unfairly allocated resources.

This paper seeks to deliberate on the National University of Samoa and Samoa Polytechnic merger and share light on challenges of delivering TVET and higher education, and how the eventual harmony between the two, inadvertently led to the conversion and birth of a Vocational University.

Introduction: Historical Background of Higher Education and TVET in Samoa

The Pacific Island nation Samoa is an emerging developing country with high ambitions for prosperity. Being the first Pacific Island nation to gain self-governance and independence in 1962, Samoa’s newly founded government quickly prioritised education and introduced more state education institutions for primary and secondary levels in the years that followed (So’o et al, 2012).

Prior to Samoa’s independence, formal education was first introduced to the nation by the missionaries who brought with them the general and theological disciplines of study. Samoa had no means of domestic higher education or technical vocational education and training (TVET) opportunities before the establishment of the theological colleges. Malua Theological College was established in 1844 by the London Missionary Society making it the second oldest theological college in the South Pacific region (Meleisea et al, 1987).

Additional theological colleges and education institutions from other Christian religious denominations were established soon after. These theological education institutions offered basic education such as English and mathematics during the formative years. As the theological education institutions developed, they offered more advanced education programs equivalent to entry and middle school secondary levels.

It was approximately during this level of maturity that some of the theological education institutions started to offer basic trainings and programs in TVET due to the absence of state education and the demand for particular skill sets such as carpentry and plumbing (Alofaituli 2011, Meleisea et al 1987, Latai 2016 & Va’ai et al 2012).

However, the training offered by the theological education institutions was somewhat rudimentary and informal. The German occupation of Samoa in 1900 saw the introduction of more informal TVET and skills training conducted by the German administration mainly for the copra farms (Bryant 1967, Droessler 2018, Hempenstall 2016, Mulder, 1980 & Firth 1977). The German administration introduced state secondary education in 1905 with Leififi College (Meredith, 1985).

It was not until after the New Zealand occupation in 1914 as a result of the First World War that a wide range of informal TVET related training was conducted by Samoans who gained their experience from the expatriates. These were not curriculum, but rather on-the-job TVET training that did not result in any form of official certification or qualification.

During all these developments, Samoa had no form of higher education delivery in the country. This was because both the German and New Zealand administrations likely saw little to no need for higher education delivery in Samoa. This is possibly for obvious reasons associated with Samoa’s deficient primary and secondary education systems at the time.

During the New Zealand administrations tenure, it was identified that there was a need to further develop the Samoan education system. Primary level education was made the main priority both in the form of curriculum and infrastructure development. The New Zealand administration established the Samoa’s Primary Teachers College in 1939 as a result (Esera, 2012).

By the year 1944, the New Zealand administration formally launched a scholarship scheme covering a maximum of eight to ten students a year. This scheme was designed to cover the final primary levels continuing up to secondary level and university. Before 1944, scholarships have been provided by the New Zealand administration as early as the 1920s but on a rather smaller scale. These earlier scholarships were not continuous and inconsistent (Meredith, 1985).

Schemes such as the one presented by the New Zealand administration were the only channels for Samoans to higher education and formal TVET. The very limited number of scholarships meant that only the students from a small number of urban based schools had access to the scheme. This led the provisional Samoan Government under the New Zealand administration to consider increasing post-primary education access in the country by establishing new intermediate and secondary schools. Samoa College was founded in 1953 with the intent to represent the pinnacle of secondary level education (Meredith, 1985).

From the establishment of Samoa College, form five and the University Entrance Exam of New Zealand represented the top level of education for the students passing through the Samoan education system. When Samoa gained independence, the Samoan Government simply continued the efforts of the New Zealand administration by further strengthening the intermediate and secondary education levels. The Samoa Secondary Teachers College was established in 1978 and later merged with the Primary Teachers College in 1990 to form the Western Samoa’s Teachers College (Esera, 2012 & Tuia et al, 2017).

The establishment of teacher colleges and the heavy emphasis on secondary education development was not isolated to Samoa. Neighbouring Pacific Islands such as Fiji, Solomon Islands and Tonga were also undergoing major education curriculum and infrastructure advances. This pushed the former colonial powers to eventually give in after considerable attempts by island governments and advocates that there was a need for PSET delivery in the region, particularly higher education (Crocombe & Meleisea 1988 & Crocombe R, 1994).

The former colonial powers agreed to establish the University of the South Pacific (USP) for the twelve English speaking islands located south of the equator (Samoa, Fiji, Tonga, Kiribati, Nauru, Niue, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, and Cook Islands), and later for the northern Pacific Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau. This was co-ordinated and funded by the joint efforts of the United Nations, Australian, British and New Zealand governments (Meleisea et al, 1987).

The USP now represented the mainstream for PSET in Samoa, but there was only one problem – the USP’s main campus was located in Fiji. The main USP campus being situated in Fiji allegedly resulted in the disproportioned benefits of the University in Fiji’s favour (Crocombe & Meleisea 1988 & Crocombe R, 1994). This eventually motivated and sparked the birth of domestic higher education and TVET delivery in Samoa.

Brief General Definition of a Vocational University

To understand the concept of a Vocational University, PSET must first be defined. PSET refers to all learning and teaching that occurs after secondary school (Skills Portal, 2017). This is inclusive of higher education, TVET and community education. According to the TVET Journal (2021), TVET ‘stands for education or training, which is technical in nature and aimed to provide skills for a person related to a profession, in order for that person to get a job and provide a livelihood’. In addition, the TVET Journal breaks down the definition of TVET by outlining the basis of each individual term as followed:

- Technical refers to: subject matters that are technical in nature, relating to hardware and software, including trouble shooting practises and engineering processes.

- Vocational relates to: an occupation or an employment, often referring to hands-on skills within professional trades.

- Education refers to: formal education, starting in high school and also including post-secondary education, such as colleges, polytechnics and universities.

- Training refers to: informal education, also called lifelong learning or continuing education, often used in initiatives of reskilling or up-skilling company staff or a wider workforce.

The more traditional and prevalent form of PSET, higher education, is defined by UNESCO (2023), as: ‘a rich cultural and scientific asset which enables personal development and promotes economic, technological, and social change. It promotes the exchange of knowledge, research and innovation and equips students with the skills needed to meet ever changing labour markets.’ However, in recent times, the changing labour markets have increasingly leaned more towards TVET, compelling initially higher education-based universities to acclimatise (Rein 2015, European Commission 2015, Hippach-Schneider 2016).

Majumdar et al (2017), in his paper titled: ‘TVET and Academic Education: A Blurring Distinction’, looks at TVET and higher education at a global context. He identifies the growing demand of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) and other science related knowledge in occupations worldwide. As a result of the huge global demand for STEM and TVET related occupations, education providers and trainers have taken notice of the importance of ‘theory-practice linked education and training’. This has resulted in a growing shift in higher education institutions adapting to TVET practice and competency-based teaching, learning and assessment methods.

The study identifies data from 13 different countries in what is described as ‘exemplary evidences’ of how emerging trends in PSET institutions have resulted in a shift from the input and theory learning to competencies and learning outcomes. Due to the growing global shift, the distinction between TVET and higher education is blurring very quickly and significantly as the two essentially become one. This is achieved ‘by converting existing normal universities into Vocational Universities’ (Majumdar, 2017).

In demonstrating the global trends, statistics from a total number of 126 different institutions showed that Vocational Universities student populations have increased significantly since 2009 as a result of recent government policies in both Asia and the United Kingdom (Rein 2015 & Majumdar, 2017). Majumdar (2017) further states that Vocational Universities in the United States have advanced significantly that there are now Ph.D. and doctoral apprenticeship programs. Universities based in Finland are now dominantly practical based in learning and assessment methods.

Other European countries such as Germany have also aligned TVET and higher education (European Commission, 2015). This clearly demonstrates that the merging and balancing of TVET and higher education programs and delivery methods is not isolated to Samoa. In fact, it has been found that the movement between higher education and TVET was more easily allied and co-ordinated through Information, Communication and Technology (ICT). This is illustrated in the below figure developed by Majumdar (et al 2017):

In the above figure, the ‘units of learning outcomes are identified in squares’; the qualifications are represented by the ‘outlined grouped units of learning outcomes’, and triangles represent the ‘add-ons’. The figure attempts to portray how courses taught across education ‘represent flexible structures’ between TVET and higher education. The ‘individual assemblage of units of learning outcomes, qualifications and add-ons is denoted by the part of the diagram shaded in yellow’ (Majumdar, 2017).

In the above figure, the different and multiple levels of squares attempt to illustrate how various courses and programs in higher education, TVET and ICT are interconnected. In Majumdar (2017) words, ‘Cross-cutting courses may combine higher education degree programs or certificate courses, but also other modules; ultimately bridging TVET and higher education courses. Add-ons are additional elements which increase the attractiveness of the learning arrangements, for example, the prospect of taking over a skilled crafts enterprise’.

Studies by Hemkes (et al. 2015), Rein (2015), Hippach-Schneider (2016) and the European Commission (2015) all identify similar views to Majumdar with overwhelming evidence that suggest that the most sustainable way forward for both higher education and TVET is a united approach which can be achieved through a customised model designed to fit the setting and context of the country, in terms of resources, its needs and social structures.

Methodology

This research is an extension of a separate study (now on referred to as the ‘principal study’) on the overall history of the National University of Samoa. The research methodology of the principal study is therefore reflected in this research. However, instead of focusing on the wider historical context of the University which was the solitary intent of the principal study, this paper narrows down and strings in considerable large elements on the National University of Samoa and Samoa Polytechnic merger which were not featured in the principal study.

This research also takes a separate narrative and data interpretative approach with the inclusion of an additional author who has no association to the principal study. Ethical clearance and authorisation to conduct research and include human participants was sought and successfully granted in 2017 by the National University of Samoa’s University’s Research Ethics Committee. In remaining within the limited timeframe and authorisation granted to the principal study, no new primary and archival sources were collected for this paper. Research literature widely available online and sourced from mainly journals are the only new resources included in this paper which do not require ethical clearance. These additional sources informed the literature and further separate this paper from the principal study.

This research utilises a mix quantitative and qualitative approach and is dominated by secondary sources that are complemented by interview informants. This research firstly takes a tentative look into existing literature within Samoa and the region to draw upon existing knowledge. It is worth acknowledging that there is a considerably limited number of up-to-date literatures specifically on the link of higher education and TVET development within Samoa.

Secondly, the research draws upon historical and archival records and data based on the National University of Samoa and the Samoa Polytechnic as the case studies. Clearance to access the Government of Samoa archival records through the Ministry of Education, Sports and Culture was not granted during the research period from 2017 to 2018. This means that this paper is limited to mainly secondary sources directly associated with the National University of Samoa. It is also vital to note that sources such as financial and council reports associated to the Samoa Polytechnic are very limited within the National University of Samoa records repository.

Interviews were used as the third and last approach. The three approaches: (1) Research Literature, (2) Archival Secondary Sources, and (3) Interviews were crossed examined in a manner where each approach informed the other. The below diagram attempts to illustrate this relationship:

Information gaps picked up during the process of dissecting the research literature and archival secondary sources informed the interview questions. Interview questions were not standardised but customised to fit the role of each participant informing the case study. Interview informants were selected based upon availability and relevance to the case study. Secondary archival sources associated with the mergers heavily informed the recommendation and selection process of the interview participants.

Only a total of seven interviews were conducted in a balance representation of the National University of Samoa and the Samoa Polytechnic. Four of the interviews were fully conducted in the Samoan language in the preference of the informants. The remaining three interviews were conducted bilingual in a mix of Samoan and English. This has limited the ability of the study to directly quote many of the accounts in the words of the interview informants. This paper also contains three interview informants who did not want to disclose their identities due to the sensitivity of the topic.

The authors although were current employees of the National University of Samoa during the time of the research, have no ingrained connection or association to the merger either in context of the National University of Samoa (or in the form of the Institute of Higher Education) or the Samoa Polytechnic (or in the form of the Institute of Technology). This is an important element in this paper as it allows the interpretation of the research data to be neutral meaning that the narration is solely objective based on the available supporting resources.

Birth of Higher Education Delivery within Samoa

What very little amount of people know about higher education delivery within Samoa was that it did not start with the National University of Samoa. Before the establishment of the University of the South Pacific, the South Pacific Regional College of Tropical Agriculture was established in Samoa with New Zealand assistance in the early 1960s. In 1977, the Government of Samoa leased the campus to the University of the South Pacific where it became the Agricultural Campus of the university with the School of Agriculture (University of the South Pacific, 2020). This became the official first widely known facility to deliver higher education within Samoa.

The following year in 1978, Samoa’s first university, ‘Iunivesite o Samoa’ which translates to ‘University of Samoa’ opened its doors at the Leulumoega Fou College campus and offered eight bachelor’s degrees ranging from education to science (Tuiai, 2012). The University of Samoa was owned and funded by the Congregational Christian Church of Samoa and operated independently from state or donor support. The opening of the University of the South Pacific Alafua Campus in 1977 and the University of Samoa in 1978 marked the official birth of higher education delivery within Samoa. No statement reflects this better than the words of the founding Vice Chancellor of the University of Samoa who would later be the founding Professor of the National University of Samoa:

In these times, there is no country, no government, no church which can retain their authority, language, and beliefs without a university. Even though it is expensive, if it is well planned the benefits outweigh the costs. There is no other educational institution that gives the true identity to a Samoan. In the same way the behaviour, the mind, the heart and language of the Europeans, Russians and Japanese is dependent on their universities.

Aiono Dr. Fanaafi Le Tagaloa, 1981 (Ripoti O Le Iunivesite O Samoa cited in Tuiai, 2012).

The University of Samoa faced a lot of challenges within its administration and from its funding body. This was particularly clear when the Congregational Christian Church of Samoa decided to send its teachers to the Western Samoa Teachers College for training instead of sending them to its own university. Tuiai (2012) in his study of the Congregation Christian Church of Samoa’s history states that ‘the Church’s neglect of the University of Samoa to train its teachers signalled the end of the university as an institution’.

By 1983 ‘the death knell for the university was sounded’ when the government announced its decision to establish the National University of Samoa (Tuiai, 2012). On February the 14th 1984, the National University of Samoa was officially opened with a total of 48 enrolled students in the University Preparatory Year program. By 1986, the University of Samoa officially ended its operations and closed its doors (Tuiai, 2012). Four years later in 1990, the National University of Samoa graduated its first-degree students. Shortly thereafter, the existing business-related night courses administered by the Samoa Society of Accountants were incorporated into the University to form the Faculty of Commerce (So’o, 2006).

The classes administered by the Samoa Society of Accountants are thought to have started in the late 1980s. The classes were however informal and offered completion certificates in various basic programs. The incorporation of the program into the National University of Samoa formalised the credentials under its new emblem as the Faculty of Commerce. In 1997, after several years of Parliamentary debate and preparation, the Western Samoa Teachers College merged with the National University of Samoa to form the Faculty of Education (Council Minutes 1997, JICA 1995 & So’o 2006).

By the end of 1997 there were only two large state funded PSET institutions left in the country, the National University of Samoa and the Samoa Polytechnic. It was not until later in 2002 that the Oceania University of Medicine was established via the Oceania University of Medicine Act chartered by the Samoan Government. The Oceania University of Medicine is a private institution and was established through an agreement between the Government of Samoa and the E-Medical Education, Limited Liability Company, International Software and Health Science Education Company based in Florida USA (Oceania University of Medicine, 2021). Since 2002, Samoa has remained with only three higher education providers who are locally based: (1) National University of Samoa, (2) University of the South Pacific and (3) the Oceania University of Medicine.

Early Professional TVET Delivery in Samoa

As stated in the introduction of this study, early TVET training started with the theological institutions in a somewhat informal approach. This was mainly due to the lack of qualified personnel and limited resources. As the programs matured and the demand for TVET skillsets increased in the late 1890s and early 1900s, the theological programs formalised (Meleisea et al 1987, Latai 2016 & Va’ai et al 2012). Outside of the theological institutions, early professional TVET delivery is thought to have started with the establishment of the Nursing School as part of the Nursing Division at the National Hospital formed in 1973 which initially provided basic technical training.

Nursing in this study is informally considered under the TVET insignia due to its large vocation and technical nature in the context of Samoa (Barclay et al, 1998). In addition, the Nursing discipline has been administered in close association with the former Samoa Polytechnic schools throughout the first decade after the 2006 merger with the National University of Samoa. When the national Nursing School was established, it offered its first Midwifery course two years after in 1975. By 1985, the first locally formal trained and certified nurses were in service and employed by the National Hospital (Barclay et al, 1998).

Prior to 1973 and the later developments, local nurses were trained as early as the 1920s-1930s informally by nurses brought in by the New Zealand administration (Barclay et al 1998 & Schoeffel 2021). Formal Maritime training is believed to have been initially set up and funded by the German Government during the mid-1970’s under its bilateral aid program to the Government of Samoa (Lene, 1997).

This led to the establishment of the Western Samoa Marine Training Centre in 1980 with the administering of the first basic maritime course for ratings. ‘The school was headed by a German superintendent with a nautical background and assisted by a technical officer with a marine engineering background. The rest of the supporting teaching staff and others were made up of local employees funded by the local government’ (Lene, 1997).

Samoa’s neighbour American Samoa who is still a colony of the United States of America introduced its first state TVET institute before independent Samoa in 1982 with the opening of the Nu’uuli Vocational Technical High School (ASDE, 2021). The Western Samoa Technical Institute was established in 1986, two years after the National University of Samoa making it the first national state funded TVET specialised institute in independent Samoa.

The Don Bosco Technical Centre, a theological institution, was opened in 1989 (Hichaaba & Newton, 2020). The Don Bosco Technical Centre was the first theological institution to specialise solely in TVET and adult continuing education and training. Fast forward to the year 1991, the Samoan Government made known its intentions of centralising its two main TVET institutions (JICA 1995 & Council Minutes 1993). By 1993, the Samoa Polytechnic was established by an Act of the Samoan Government as the successor to the Western Samoa Technical Institute and the Western Samoa Marine Training Centre which by this time no longer received direct financial and human resource support from the German Government (Council Minutes 1993, Lene 1997 & So’o 2006).

The merger of the Western Samoa Technical Institute and the Western Samoa Marine Training Centre to form Samoa Polytechnic saw the introduction of new programs outside of the traditional trades and TVET disciplines. This included new certificate and diploma programs in the Schools of Business and General Studies, Hospitality, Journalism and Tourism in addition to the establishment of the School of Engineering (JICA 1995 & So’o, 2006). Correspondingly in 1993, the National Nursing School came under the umbrella of the National University of Samoa to form the Faculty of Nursing (Council Minutes 1993 & So’o 2006). By the year 1998, the Samoa Polytechnic and the National University of Samoa were the last two remaining large state funded PSET providers in the country.

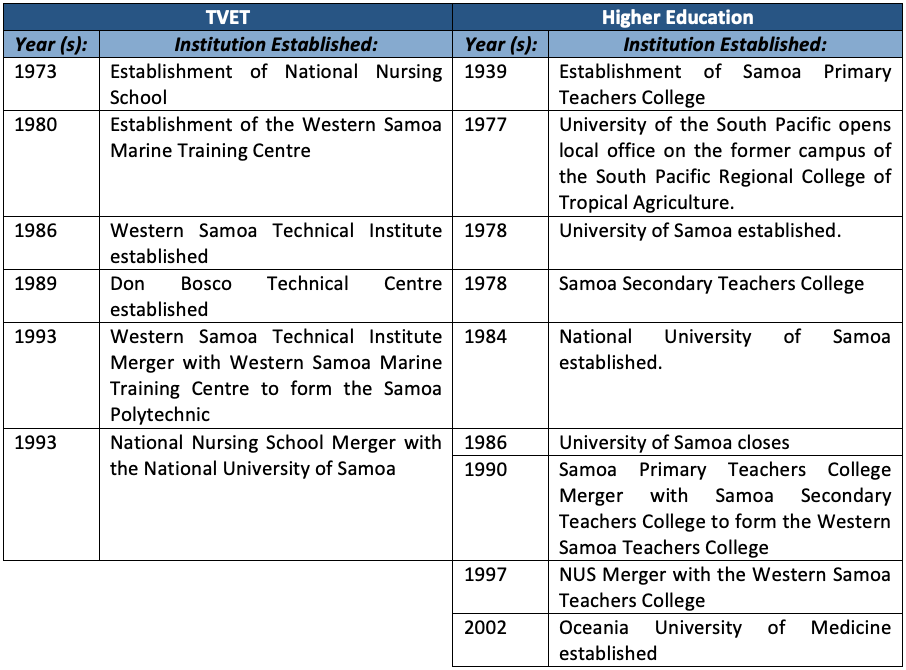

The below diagram is a side by side comparison of the higher education and TVET timelines:

Merger of the National University of Samoa and the Samoa Polytechnic

It was not until the year 2001 that the Government of Samoa officially made known its intentions of merging the National University of Samoa and the Samoa Polytechnic. In addition to the standing agenda to centralise all state funded PSET institutions, the Government was also motivated due to what was described as growing and persistent financial and operational struggles of the two institutions (Council Minutes, 2001). It was believed that the merging of the two institutions would firstly decrease government expenditure by the merging of the budgets.

Secondly, it was believed that the merger would alleviate the administrative and operational turmoil’s as the National University of Samoa and the Samoa Polytechnic administrations will be joined. As a result of later Parliamentary debate, a scope exercise was conducted to investigate the realities of merging the two institutions. This led to the Samoa Polytechnic and National University of Samoa signing the ‘National University of Samoa Joint Cooperation Agreement’ in 2001 which outlined the potential merger between the two institutions (Council Minutes, 2001).

In response to the Government decision, the National University of Samoa Council put together an ad hoc committee to conduct a ‘fact finding mission’ researching case studies of similar mergers in New Zealand and Australia. The ad hoc committee’s main purpose was to determine which of the options best suited the National University of Samoa and the Samoa Polytechnic (Council Minutes, 2002a). The options identified by the National University of Samoa Council of 2002 are as follow: (1) a full merger, (2) a takeover or, (3) an alliance. The findings favoured a merger between the two institutions and referenced an unspecified successful case in New Zealand where the merger between a small TVET and higher education institution similar to the scale of National University of Samoa increased the status of the institution, the credibility of the programs and the funding (Council Minutes, 2002b).

By 2003, the report resulting from the Government scope exercise investigating the merger recommended the construction of new facilities to house the Samoa Polytechnic and the combined administration of both institutions (Council Minutes, 2003 & JICA, 2010). In response to the report, the Government of Samoa approached the Japanese Government for assistance through the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) which previously constructed the development of the National University of Samoa Le Papaigalagala Campus in 1997 (Council Minutes, 2003 & JICA 1995).

It was not until mid-2004 that JICA granted the Government’s request and proceeded with the construction of the Le Papaigalagala Campus extension (Council Minutes, 2005a). With the merger physically starting to take shape in terms of infrastructure, the NUS Council quickly recognised the need to formulate a new Act and started proceeding with informed negotiations with the Samoa Polytechnic Board (Council Minutes, 2004a).

It was during the early negotiations that it was uncovered and acknowledged by both governing bodies that the merging of the TVET and higher education systems was more difficult than anticipated due to the significant differences between organizational, program and curriculum structures (Council Minutes, 2004b & Council Minutes, 2005b). It was eventually decided that the two institutions will remain in the current structures but to co-exist, a decision that will have almost immediate unforeseen consequences in the years followed.

By 2006, the Government of Samoa approved the third National University of Samoa Act officialising the National University of Samoa Act 2006 (Council Minutes, 2006a & Council Minutes, 2006b). The National University of Samoa Act 2006 was ‘an Act to merge the National University of Samoa and the Samoa Polytechnic as one institution and to repeal the National University of Samoa Act 1997 and the Samoa Polytechnic Act 1992/1993’ (National University of Samoa Act, 2006). It was noted that ‘this Act establishes the National University of Samoa as an institution combining the former National University of Samoa and the former Samoa Polytechnic’ (National University of Samoa Act, 2006). Due to the merge, the National University of Samoa Act 2006 included new functions that represented the functions of the former Samoa Polytechnic.

The Act also featured changes in the composition of the National University of Samoa Council with the inclusion of representatives from the Samoa Polytechnic Board and the introduction of the two new Deputy Vice Chancellor roles. The Deputy Vice Chancellor for the Institute of Higher Education was introduced to head the former National University of Samoa faculties, while the Deputy Vice Chancellor for the Institute of Technology was to head the former Samoa Polytechnic schools.

It was through the Deputy Vice Chancellor Institute of Technology that the former Samoa Polytechnic basically remained in its previous form but under the umbrella of the National University of Samoa. Thus, the institutions were technically still separated but merged in a coexisting manner. This system eventually inadvertently disadvantaged the TVET programs within the University.

The Unintended Systematic Separation of TVET and Higher Education

It was not until 2008 that the University standardised its salary scale across the Institutes of Technology and Higher Education. Since the merger, the TVET staffs were paid in the original Samoa Polytechnic salary scale which was considerably lower than that of the higher education staff. The efforts to standardise the salary scales in favour of TVET staff did not come without its hurdles and challenges. The general argument against the standardised salary scale was that the staff teaching TVET programs at the time did not have bachelor degrees in comparison to higher education staff that possess degrees and higher qualifications.

This argument was eventually overturned, and the standardised salary scale was implemented with the condition the University up-skill and upgrade the qualifications of its TVET staff (Anonymous 3 Interview 2018, Council Minutes 2008 & So’o 2018). By the year 2009, the University welcomed its fourth Vice Chancellor Dr. Asofou So’o after 11 years under Magele Maliliu Magele leadership, who was the former head of the Samoa Polytechnic (Council Minutes, 2009a & Council Minutes, 2009b).

It was during this era that the University made drastic changes to its structure in an attempt to alleviate the frictions that inadvertently formed between the former National University of Samoa and the Samoa Polytechnic internally three years on from the merging in 2006 as a result of unintended systemic separation. Since the merger, there was seemly growing prevalence of a perception within the institution and the close associated community that the higher education faculties and its programs were of greater merit in comparison to the schools in the Institute of Technology.

It has been suggested that it was reflected in the internal ministration of individuals, programs and resources (Anonymous Informant 1 2017, Anonymous Informant 2 2017, Anonymous Informant 3 2018 & So’o 2018). The friction between TVET and higher education was never prodigious or anything major but was simply a perception, an idea that one was greater than the other. In fact, Temese (2018) claims that most individuals between the two institutes personally got along very well despite the program and structural differences.

It is very likely that the perception affected morale and behaviour which in-turn may have affected decision making, policy development, governance and strategy. However, this perception was not confined to the University as it was also reflected by the general Samoan public who preferably have their students enrolled in the higher education programs in contrast to that of the Institute of Technology (JICA 2010 & National University of Samoa Statistical Digest 2019). Temese (2018) describes – how freshmen students would take pride in making the higher education entry level while the students with not so impressive grades were referred to the Institute of Technology.

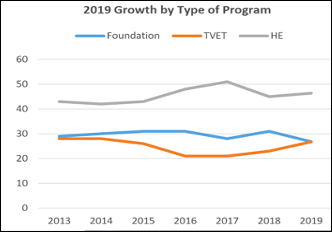

Thus, the Institute of Technology may have likely been associated with social indignity in comparison to the Institute Higher Education which was associated with social pride and prestige. According to the University enrolment numbers, the TVET programs appear to have played second to that of higher education (JICA, 2010, So’o 2018 & National University of Samoa Statistical Digest 2019). The below chart demonstrates the student population growth and trends from 2013 to 2019. The TVET programs clearly feature below that of higher education.

In addition to the interpretation of recent enrolment figures, a report developed by JICA (2010) as a follow up investigation to infrastructure developments of the merger in 2006 also claims that there was a public perception issue which did not favour the TVET programs. The report to some extent, also recognises the internal disparity between the TVET and higher education programs by acknowledging the University’s role and potential influence it has in changing the current circumstances. This is clearly described in the following statement highlighted in the report:

The reasons for the unpopularity of some of the TVET programs could be a lack of direct promotion activities to secondary schools by the N.U.S itself and also the negative image held by high school students against some programs of the School of Engineering, such as welding and fabrication and plumbing and sheet metal… JICA, 2010

The report adds that another major contributing factor is the lack of job opportunities and lower salaries at the time offered to TVET related jobs compared to the more popular higher education opportunities (JICA, 2010). However, this has shifted in recent years with the skill demand, Government and donor support for TVET specialised roles increasing both within the country and the region (So’o 2018 & MESC 2018).

The Restructure: Removing the Systematic Separation between TVET and Higher Education

To improve the discrepancies between TVET and higher education, the first major area targeted by the University’s administration was a restructure. By 2010, the National University of Samoa Amendment Act 2010 was approved by the Cabinet. The Amendment Act 2010 was ‘an Act to amend the National University of Samoa Act 2006’ (National University of Samoa Amendment Act, 2010). The amendments included repealing definitions to multiple sections of the National University of Samoa Act 2006. This also included changes in reporting, policy and administration procedures (Council Minutes, 2011a & Council Minutes, 2011b).

Perhaps the most influential and controversial change was with the roles of the two Deputy Vice Chancellors, renaming the Deputy Vice Chancellor Institute of Higher Education to Academic and Research; and the removing the Deputy Vice Chancellor Institute of Technical in favour of a Deputy Vice Chancellor for Corporate Services. The restructure was described by the Council Minutes (2015a) to allow the Vice Chancellor to focus on more vital areas like policies and political engagements, while the Deputy Vice Chancellors handle the administrations for both academic and corporate services.

Due to the changes in the National University of Samoa management system, the university centralised its control and improved its monitoring significantly. The NUS Council of 2011 believed that the changes at the senior management level have tremendously impacted and benefitted the lower levels that follow; providing a system that is more transparent and consistent with expectations of higher education institutions. So’o (2018) claims that one of his core motives for inciting the changing of the Deputy Vice Chancellors for the Institute of Technology and the Institute of Higher Education to the roles of Deputy Vice Chancellor of Corporate Service and the Deputy Vice Chancellor of Academic and Research was a good move to ‘eliminate the separation between the former Samoa Polytechnic and N.U.S teaching staff’.

So’o (2018) described the previous separation between the TVET and higher education staff as a ‘toxic environment for the university staff’. The change helped unify the teaching staff by eliminating the trade’s school system and introducing a faculty system aligning the former Samoa Polytechnic schools with the rest of the University. This gave birth to the Faculty of Applied Science which was a combination of all the trades’ schools and the School of Nursing but did not include the School of Maritime Training which maintained its detachment due to its distinctiveness. The Faculty of Applied Science was later rebranded to the Faculty of Technical Education in 2018 when the School of Nursing separated itself to join the School of Medicine and form the Faculty of Health Science (Council Minutes, 2018).

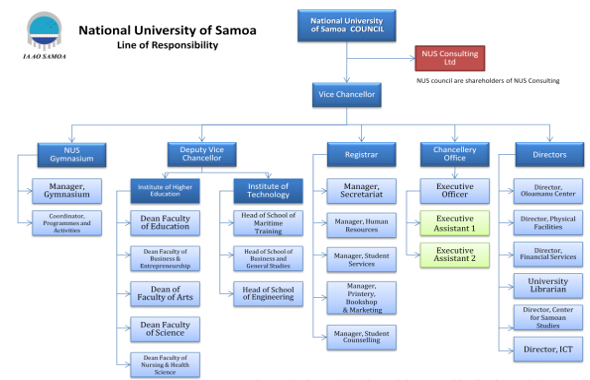

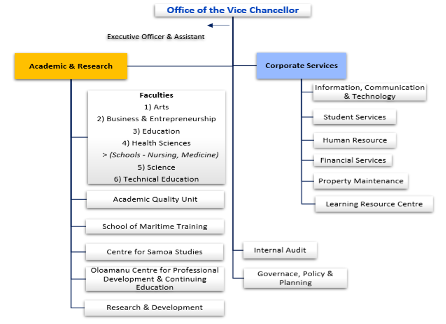

Below are illustrations of the National University of Samoa Organizational Structures from the years 2006 to 2014 and years 2014 to 2019. The below diagrams demonstrate the change and shift in managements structures with the systemic separation of higher education and TVET in 2006 and the unification as identified in the 2014 model.

National University of Samoa Organizational Structure 2006-2014

Source: NUS Annual Report 2009

National University of Samoa Organizational Structure 2014-2019

Source: National University of Samoa Corporate Plan 2017-2020

The large scale of changes in an attempt to improve the University’s academic and corporate administration and ease the virulent environment between the TVET and higher education programs received a lot of resistance from both sides of National University of Samoa staff (Council Minutes, 2014a). The resistance was eventually eased when it became evident that the new changes significantly improved the National University of Samoa academic and corporate operation and more importantly, unified the TVET and higher education programs as one (Council Minutes, 2014b).

Now there was no longer a systemic separation between the former Samoa Polytechnic and higher education staff. The restructure systematically changed the former Institute of Technology making it similar and equal to the existing higher education faculties. The changes were simply an alteration to job titles and organization structure and did not affect the delivery system and essence of the TVET programs. In the nature of any change, it takes time for the perquisites to fruit.

According to an account of one source (Anonymous Informant 1 2017) who wished to remain anonymous, the Institute of Technology initially believed that they were being mistreated and in disadvantage, particularly because their Deputy Vice Chancellor post was scrubbed and replaced with Corporate Services while the Deputy Vice Chancellor of the Institute Higher Education was simply rephrased to Academic and Teaching. The source goes on to claim that it was not until a year or two after the restructure that TVET staff could ‘see the positive changes with the small things first’.

We were no longer being referred to as I.O.T, we no longer had separate meetings, we were no longer the ‘other guys’ of N.U.S Anonymous Informant 1, 2017

Argument: Disparity in Resource Allocation between TVET and Higher Education

The accounts of another anonymous source (Anonymous Informant 3, 2018) who was a former staff member of the University during the Institute of Technology era gave a description of the institution now looking from the outside. It was argued that Samoa Polytechnic would receive direct large amounts of funding from donors for its programs. In contrast to when the institutions merged, the donors’ funds are mixed into the overall University grant from Government which is then dispersed to all the faculties, suggesting that the TVET programs only get a fraction of the resources they once did (Anonymous Informant 3, 2018).

In a comparison of the Samoa Polytechnic budget in 2005 (one year before the merger) and the Faculty of Technical Education budget in 2017 (budget at the time of the interview informants claim), this statement can be argued as true to an extent but also largely incorrect even when considering inflation (Samoa Polytechnic 2005 & VCC 2017). In terms of operational budget, TVET allocation has decreased in comparison to its Samoa Polytechnic years. This is because the large sum of operational budget is divided to the larger University. The operational budget is divided to administrative sections that specialise in overseeing maintenance, ICT, and corporate operations.

However, the decrease in the operational budget is arguably in no way a loss. This is because the combining of the administrations likely resulted in its improved delivery, which was one of the motives behind the Governments push for the merger as highlighted earlier in this study. In addition, areas such as ICT that the NUS possess much greater competency in are now available to the benefit of the TVET programs. In another argument point, assets such as vehicles that were subject to the sole usage of the TVET programs now have to be shared with the rest of the institution. In terms of individual value, TVET programs are actually getting less from the assets such as vehicles than they previously did.

In terms of collective value, the resources which were once confined to limited use by TVET programs now catered to a wider set of programs. In a comparison of the TVET budgets to its higher education counterparts, the operational budget for the TVET programs well exceeds that of most of the higher education faculties besides that of Health Science (Council Minutes 2017b, Council Minutes 2018 & VCC 2017). This is because TVET programs in general cost more to deliver in comparison to the majority of its higher education counterparts.

TVET programs such as Joinery, Plumbing and Welding require the purchase of consumable materials such as pipes and timber not including safety materials, expensive machinery and the high use of electricity. In contrast to higher education, a program in the humanities or economics simply only requires the University to provide the venue and lecturer in addition to study resources which the students traditionally pay for themselves. Based on the interpretations of this study, there is no unfair distribution of operational resources.

The TVET programs personnel budget for its teaching staff has actually increased significantly in comparison to the Samoa Polytechnic due to the 2008 standardisation of the salary scale. If we are to just weigh the comparison in collective value and not by individual numerical figures, the TVET programs have actually benefited much more during its merge with the University in comparison to the Samoa Polytechnic era. The 2006 extension project carried out by JICA provided 6 state of the art facilities solely for TVET programs.

In 2015, the Peoples Republic of China constructed a large three storey building campus at Mulinu’u to house the School of Maritime Training (Council Minutes 2007 & Keresoma 2015). This also includes the allocation of resources such as a vehicle, a teaching simulator and equipment. The majority of higher education programs share the large campus facility that was constructed by JICA in 1997.

So, in terms of infrastructure, the TVET programs have actually benefitted tremendously more in comparison to their higher education counterparts. In terms of space, the TVET programs collectively mass approximately 47,064.28 square meters in space in comparison to the rest of the programs that share a space area of approximately 26,552.56 square meters. This is keeping in mind the higher education programs hold the majority of student enrolment numbers.

The only actual value that the TVET programs have lost from the Samoa Polytechnic era is the privilege of administrating and accessing its own resources without having to bid with contending faculties. So, it seems clear that the claim of Informant 3 based on the resources available to this study is rather a personal opinion than fact. However, an in-depth 10-year analysis of financial documents, physical assets and infrastructure of the Samoa Polytechnic will have to be taken in a side-by-side comparison of the pre-merger and post-merger era.

This is a highlighted weakness of this study as Samoa Polytechnic financial documents 10 years before the merger are not available in the records of the University. Also, there is no proper record of pre-merger physical assets and its market value at the time of purchase. This is likely due to the rushed transition during the 2006 merger which possibly resulted in the misplacement and loss of Samoa Polytechnic records, a problematic feature which previously occurred during the NUS and Western Samoa Teachers College merger in 1997 (National University of Samoa 1997 & Tunupopo 2018).

In addition, the rejection of access to Government records has furthermore limited this study’s ability to capture any direct records of the Samoa Polytechnic. This study only takes an individual year comparison of Samoa Polytechnic 2005 and the University financial records of 2017, a 12-year margin. It is likely that a more detailed analysis may never be available simply due to the lack of pre-merger official documentation of the Samoa Polytechnic.

Moving forward from the disparity in resource allocation argument, Informant 3 (2018) goes on to say that ‘seeing the bigger picture was easier once you are out of the institution and watching from afar’.

We had a rough time after the merge in 2006, I take my hat off to this guy Fui[1], what he did was brave. I now and then speak to my former workmates and I see things are better. Anonymous Informant 3, 2018

An alternative source who also wished to remain anonymous (Anonymous Informant 2, 2017) reflected a similar opinion with the other two interview informants regarding the eventual benefits of the restructure but voiced strong disagreement with how it (the restructure) was handled. In any drastic change in an organization, particularly if it involves reclassification of roles, there is always individuals that benefit and ones that lose out.

All organizational restructures have pros and cons with individuals or groups more often than not are affected negatively by the changes (Leon et al 2020, Andersson et al 2014 & Nedovic et al 2013). Ultimately, a restructure or any change in general will not please everyone. The goal is not to get everyone to agree but to get to the point where the least amount of people disagree with the restructure, particularly if the organization at large is the ultimate beneficiary. In the case of the National University of Samoa, its certainty does seem so.

Political Pressure for the Separation of the former Samoa Polytechnic from the National University of Samoa

Leading up to 2017, the University worked closely with the Ministry of Education Sports and Culture, the Samoa Qualifications Authority and other PSET providers in developing the National TVET Strategy. The National TVET Strategy was passed by the Government in 2017. The strategy endorsed National University of Samoa as the main focal point for TVET development in the country, an instrumental milestone for the institution and TVET in Samoa (Council Minutes, 2017b).

Unfortunately, this milestone was short lived as political pressure mounted onto the University in early 2018. On February 24th 2018, an article was published in the Samoa Observer (2018) based on Parliamentary discussions which were held on the 23rd of February. The article states: ‘Member of Parliament for A’ana Alofi No. 3, Ili Setefano Ta’ateo, has called upon the government to consider separating the National University of Samoa (N.U.S.) and the Institute of Technology (I.O.T.)’. The article further states that ‘Ili said he has noticed that since the University and I.O.T. merged more than 10 years ago, a lot of the focus has been dedicated to the University rather than I.O.T.’.

The Member of Parliament pushed the agenda for the Government to ‘reconsider separating the entities again, to ensure the focus and resources are channelled towards the development of vocational learning’. The Member of Parliament further argued that TVET ‘cannot afford to play second fiddle to the more popular subjects being taught at the University’, in other words, the higher education programs. The proposal was supported by a considerable number of MP’s (Samoa Observer, 2018). Prior to this article, the University in the past has received pressure from the Government on a number of occasions for the separation of the Samoa Polytechnic from the National University of Samoa (Anonymous Informant 2 2017, Council Minutes, 2017a & So’o 2018). Pressure that has been grounded on what this paper can suggest are well out-dated claims.

The Government, through its Parliamentary committee requested that the University have an independent review of the former Samoa Polytechnic and National University of Samoa to determine whether a disaffiliation of the two institutions was necessary (So’o, 2018). This request has yet to be fulfilled likely due to the University’s change in management in 2019. However, it is believed that a lot of the Government ventures at separating the former Samoa Polytechnic from National University of Samoa although well intended, was motivated by its members who were formerly employed to either the Samoa Polytechnic or under its form as the Institute of Technology (Anonymous Informant 2 2017, Anonymous Informant 3 & So’o 2018).

It is suggested that the Members of Parliament who were formerly tied to the Samoa Polytechnic and the Institute of Technology were ‘stuck in the past and unaware of significant changes that have occurred since they have left’ (Anonymous Informant 3 2018). This is evident in the Samoa Observer article which quotes the Member of Parliament referencing ‘I.O.T’, a term that has not been used formally in National University of Samoa for at least four years from the date of the article.

The term of Institute of Technology or I.O.T now seems to represent the once and recent past of the University, the division between TVET and higher education. Since the unification of TVET and higher education under one Deputy Vice Chancellor, there has been no more organization or systemic separation between TVET and higher education. The TVET programs were now operating as just another faculty and being an integral part of what is now a Vocational University.

Moving onto Greener Pastures: The Fruits of a Vocational University

So’o (2018) agreed that external or government pressure on TVET programs is good, despite its political motivation. He believed that it helps provide an extra motivational push to the TVET initiatives already pursued by the University. ‘Even though things are good in comparison to what they used to be, they can be better’ (So’o, 2018). So’o also signifies how TVET and higher education co-exist and complement one another and how one needs the other. ‘TVET programs act as a net for universities to capture the students who do not qualify for higher education programs and prepare them for the increasing demand in the public and private sectors’ (So’o, 2018).

The University in late 2018 launched its Research Plan 2018-2023 which identified TVET as one of its primary research priorities alongside health and technology (‘National University of Samoa Research Plan 2018 – 2023’, 2018). This was a milestone for the University because up to 2018, research at National University of Samoa was traditionally conducted by higher education and was not expected from the TVET programs. The University has also continued up-skilling its TVET staff at the Australia Pacific Training Coalition and New Zealand. As more TVET staff return with undergraduate and higher degrees, naturally their research capacity will increase.

The University also launched the Bachelor TVET program offered by the Oloamanu Centre for Professional Development and Continuing Education, a significant achievement for the institution. This was the first Bachelor program of its kind at the University and within the country. The University has continued to offer new TVET programs that align to development priorities such as renewable energy. The strategic alignment of these programs with development priorities will tactically draw in external support and resources.

The University has better integrated TVET programs into its Faculty of Science and Faculty of Business and Entrepreneurship which both have the capacity to carry out high level research and delivery. The University has also strengthened its ties with the Samoa Qualification Authority in an agreement to nationally accredit all of its TVET programs in efforts to increase its quality. By 2021, the University had moved to its fifth Vice Chancellor, Professor Alec Ekeroma, formerly the founding Professor of Medicine. Professor Ekeroma, being essentially new to the institution and not tied to the previous separation of National University of Samoa and Samoa Polytechnic, proved to be good for the University in terms of impartiality.

Within one year of Professor Ekeroma’s tenure, the University increased the accessibility to its TVET programs through offering scholarships funded by Australia and New Zealand via the Education Sector Support Program fund. The scholarships strategically target disadvantaged groups such as people with disabilities, women and the unemployed. As a result, TVET enrolment for semester one 2021 had increased by a staggering 300per cent (VCC, 2021), well exceeding the numbers in the Samoa Polytechnic and I.O.T era. The University also reached record overall enrolment numbers that year. In addition to the increase in TVET enrolment numbers, the spike in overall student figures is also likely due to the Covid-19 Pandemic which closed the boarders and encouraged students whom traditionally study at metropolitan institutions to consider the local university.

However, the large and sudden increase in TVET enrolment figures will not come without its challenges. There will likely be long term resource and staffing implications. Sustainability will also be an issue as the scholarships are externally funded and can easily be subjected to alterations. Another issue is the authenticity of student enrolment in its purest form.

The motive behind why the students are taking up the opportunity. It has been suggested in this study that higher education programs have traditionally been more popular with the community with the majority of its enrolment for at least the past decade being self-funded. If students enrolling into TVET programs are doing so simply because it is a free opportunity, the scholarship scheme will likely not fruit well if it eventually comes to an end.

Long term continuous in-depth promotional programs will have to be implemented strategically at the primary and secondary levels and within the community as suggested in the JICA 2010 report. These promotional programs must target behaviour change by having the ideological transformation groomed into the primary and secondary education systems. It may take time to fruit but it will eventually result in a perception shift which should encourage an increase in the TVET programs popularity, meaning that more people will pursue TVET opportunities based on preference rather than necessity or simply because it is free. Scholarships implemented alongside a proper in-depth promotional program will make the University’s efforts sustainable.

The days of when TVET were seen as inferior to higher education are now a memory. It is clear that the TVET programs are now moving into pastures greener than that they ever experienced before. Evidence from this research clearly conclude that the friction between the higher education and TVET at the National University of Samoa was a result and impact of structural and systematic influence rather then it being motivated by discrimination. When the system and organizational structure changed, the institutional divide between higher education and TVET dissolved with time.

Time is a crucial element in any stem of change. With time, the individuals employed by the University have gotten used to the new system and therefore resulted in a change of practice and perception. These changes in perception will surely trickle down to the communities with increasing awareness and proper promotional campaigns to run alongside scholarships. With time, the former separation between Samoa Polytechnic and National University of Samoa will be nothing more than historical research literature as a new generation of younger scholars and administrators who see the University as one institution and not two, eventually fill in the shoes of their predecessors.

Acknowledgements

This paper is an extension from chapters of the primary authors Masters of Development Studies thesis titled ‘The Five Tala University: Higher Education in Developing Countries: A Case Study of the National University of Samoa’. Although the majority of the data for this paper was originally collected in 2017-2018, the lion’s share was not featured in the thesis due to it being irrelevant to the overall topic and focus of the paper. We would also like to acknowledge Faith Manuleleua and Lorian Finau-Groves for her editorial assistance.

References

[1] Informant referencing Asofou So’o by his chiefly title

Alofaituli, Brian T. (2011) Language Development Curriculum within the Samoan Congregational Churches in the Diaspora. University of Hawaii.

Anonymous Informant 1. (2017). Interview/Personal Communication.

Anonymous Informant 2. (2017). Interview/Personal Communication.

Anonymous Informant 3. (2018). Interview/Personal Communication.

ASDE. (2021). Nu’uuli Vo-Tech High School (1982) of American Samoa. American Samoa Department of Education, accessed 11-02-21, http://nevisoblogi.phpweb2.neviso.fi/wp-content/blog/american-samoa-department-of-education-9b3130

Barclay, L., Neilson, F. & Stowers, P. (1998). Samoan Nursing: The Story of women developing a profession’, Allen & Unwin, ISBN 1 86448 585 X.

Bryant, Nevin A. (1967). Change in the Agricultural Land Use in West Upolu Western Samoa. University of Hawaii.

Crocombe, Marjorie & Meleisea, Malama. (1988). ‘Pacific Universities: Achievements, Problems and Prospects’, published by the Institute of Pacific Studies University of the South Pacific, Suva, pg. 119

Crocombe, Ron (1994). Post-Secondary Education in the South Pacific: Development in the Small States of the Commonwealth Series. Commonwealth Secretariat, London, pg. 23

Council Minutes (1993). 9th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, December 2nd – 3rd

Council Minutes (1997). 16th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, March 20th – 21st

Council Minutes (2001). 25th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, September 13th

Council Minutes (2002a). 26th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, March 13th -14th

Council Minutes (2002b).27th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, September 12th – 13th

Council Minutes (2003). 28th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, March 27th -28th.

Council Minutes (2005a). 32nd Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, March 10th – 11th

Council Minutes (2005b). 33rd Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, September 8th – 9th.

Council Minutes (2006a). 34th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, March 9th -10th.

Council Minutes (2006b). 35th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, September 7th – 8th.

Council Minutes (2006c). Interim Meeting of NUS and Samoa Polytechnic Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, February 7th – 13th.

Council Minutes (2007). 36th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, March 7th – 8th.

Council Minutes (2008). 39th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, September 10th – 11th.

Council Minutes (2011a). 43rd Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, 16th – 17th September.

Council Minutes (2011b). 44th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, 15th-16th September.

Council Minutes ( 2017a). 54th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, 5th– 6th April.

Council Minutes (2017b). 55th Meeting of Council Minutes. National University of Samoa, 5th – 6th October.

Council Minutes (2018). National University of Samoa Council 56th Meeting. National University of Samoa, October 4th – 5th.

Droessler, Holger. (2018). Copra World: Coconuts, Plantation and Cooperative in German Samoa. Journal of Pacific History.

European Commission (2015). Study on Higher Vocational Education and Training, Revised Final Report. ICF International, Brussels

Esera, Epenesa (2012). Teacher Education in Samoa’, Improving education systems: quality and leadership, Commonwealth Education Partnerships, pg. 93 – 94, accessed 01-05-2021, http://www.cedol.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Teacher-education-in-Samoa-Esera.pdf

Firth, Steward (1977). The Dispute over Chinese Labour in German Samoa. New Zealand Journal of History.

Hemkes, B; Wilbers, K; Zinke G. (2015). Brücken zwischen Hochschule und Berufsbildung durch bereichsübergreifende Bildungsgänge (aus) bauen. In: BWP 3/15.

Hempenstall, Peter J. (2016). Pacific Islanders Under German Rule. Australian National University.

Hichaaba, Lauren & Newton, Tina (2020). Idyllic Samoa holds hidden struggles. Catholic Outlook, accessed 07-01-2020, https://catholicoutlook.org/idyllic-samoa-holds-hidden-struggles/#:~:text=schools%20and%20parishes.-,Don%20Bosco%20Technical%20Centre%20(DBTC)%2C%20the%20first%20Salesian%20school,been%20successful%20in%20mainstream%20schooling.

Hippach-Schneider, U. (2016). Academisation or vocational draft? In BIBB BWP, special edition 2016.

JICA (1995). Basic Design Study Report on the Project for Establishing the New Campus for the National University of Samoa in Western Samoa. Japan International Cooperation Agency, Yamashita Sekki Inc, pg. 1 – 29

JICA (2010). Ex-Post Evaluation of Japanese ODA Grant Aid Project: “The Project for Upgrading and Extension of Samoa Polytechnic. Japan International Cooperation Agency, Ernst & Young Advisory Co., Ltd, pg. 1 – 22

Latai, Latu (2016) Covenant Keepers: A History of Samoan (LMS) Missionary Wives in the Western Pacific from 1839 to 1979. Australian National University.

Lene, Perive Tanuvasa. (1997). A Review and Evaluation of the Maritime Training and Education Conducted for Ratings at the Marine Training Center, Western Samoa, and the Changes Required to Comply with the STCW95. World Maritime University Dissertations. 1056. https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/1056

Majumdar, Shyamal & Rein, Volker (2017). TVET and Academic Education: A Blurring Distinction – New Opportunities for the Future, Scholarly Technical Education Publication Series 9STEPS), Volume 3, Colombo Plan Staff College, accessed 01-24-2022, https://www.cpsctech.org/2017/07/tvet-and-academic-education-blurring.html

Meleisea, Malama et al. (1987). Lagaga: A short history of Western Samoa, edited by Meleisea, M. & Meleisea P. S., published by University of the South Pacific Suva, pg. 52 – 87

Meredith, Uili Tau’ili’ili. (1985). The National University of Samoa Annual Report in Founding Year, 1984: First Annual Report of the University. Government of Western Samoa, pg. 2 – 29.

MESC (2018). National Schools Technical and Vocational Education Training Policy 2018 – 2023. Ministry of Education, Sports and Culture. Government of Samoa.

Mulder, Yvonne M. (1980). Western Samoa and New Zealand: Small State – Large State Relations. University of Canterbury. New Zealand.

National University of Samoa (1997). Annual Report 1984 – 1997. National University of Samoa. pg. 6.

National University of Samoa. (2009). Annual Report 2009. National University of Samoa.

National University of Samoa (2017). The National University of Samoa Corporate Plan 2017-2020. National University of Samoa.

National University of Samoa. (2018). The National University of Samoa Research Plan 2018-2023. National University of Samoa. Accessed 01-03-2021, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1B95UEwnB34S2FOIMwMa6sYqWNO6jg37-/view

National University of Samoa. (2019). NUS Statistical Digest 2019, National University of Samoa. Accessed 01-03-2021, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1LTE8iDs155JDNMPIx5EieLDdQZixcEbR/view

National University of Samoa Act (2006).National University of Samoa Act 2006, pg. 2 – 7

Oceania School of Medicine (2021). OUM’s Roots. Accessed 15 February 2021, https://oum.edu.ws/samoa/

Keresoma, Lagi (2015). School Of Maritime Training and Marine Research Opens In Samoa. Pacific Islands Report.

Rein, V. (2015). Permeability promoting aspects of qualification design at the interface of vocational and higher education in the context of the shift to competency oriented learning outcome. BIBB

Samoa Observer. (2018). M.P. calls for separation of N.U.S. and I.O.T. Accessed 02-18-2021, https://www.samoaobserver.ws/category/samoa/6721

Schoeffel, Penelope (2021). Email Correspondence, Monday February 5.

Skills Portal (2017). What is Post School Education and Training? The Skills Portal. Accessed 01-24-2022, https://www.skillsportal.co.za/content/what-post-school-education-and-training

So’o (2018). Interview/Personal Communication.

So’o, Asofou et al (2012). Political Development. Samoa’s Journey 1962-2012, Aspects of History. National University of Samoa. Victoria University Press.

So’o, Asofou. (2006). The National University of Samoa History. International University Sports Federation, accessed 07-01-2020, http://www.fisu.net/medias/fichiers/national_university_of_samoa.pdf

Taise, Malua (2007). Secondary School Teachers Perceptions of the In-Service Training Program in Samoa. Unpublished Master of Education Thesis, University of the South Pacific.

Temese (2018). Interview/Personal Communication.

Tunupopo (2018). Interview/Personal Communication.

Tuia, Tagataese T. and Schoeffel, Penelope. (2017). Education and Culture in Post-Colonial Samoa. Journal of Samoan Studies. Volume 6. National University of Samoa.

Tuiai, Aukilani (2012). The Congregational Christian Church of Samoa, 1962–2002: A Study of the Issues and Policies that have Shaped the Independent Church. Unpublished thesis submitted to Charles Sturt University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, June 2012, pg. 120 – 158

TVET Journal (2021). TVET definition: the TVET meaning and what it stands for. TVET Journal, accessed 01-24-2022, https://tvetjournal.com/tvet-systems/tvet-definition-the-tvet-meaning-and-what-it-stands-for/

UNESCO (2023). Why does higher education matter?, accessed 11/03/2023, https://www.unesco.org/en/higher-education/need-know

University of the South Pacific (2020). History of Alafua Campus. The University of the South Pacific, viewed 05 January 2020, https://www.usp.ac.fj/index.php?id=5681

Va’ai, Emma Kruse et al. (2012) Religion. Samoa’s Journey 1962-2012, Aspects of History. National University of Samoa. Victoria University Press.

VCC (2017). Vice Chancellors Committee Meeting Minutes. National University of Samoa, July 2017.

VCC (2021). Vice Chancellors Committee Meeting Minutes. National University of Samoa, February 18 2021.